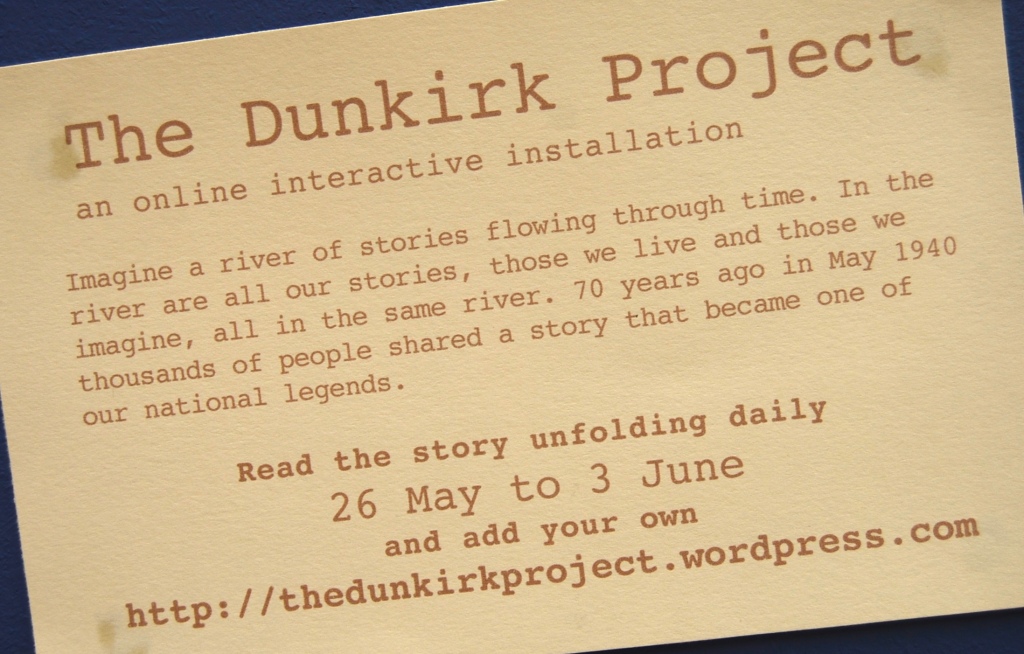

The Dunkirk Project

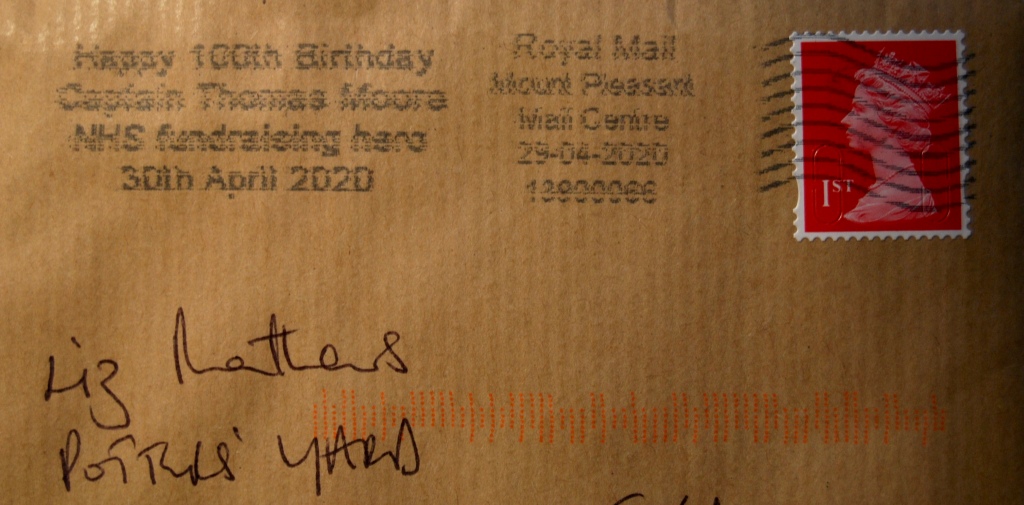

by Liz Mathews

Third edition, revised in 2023 and regularly updated

On Sunday 26th May 1940 the first ships sailed from Dover to rescue a vast crowd of British and French troops and refugees stranded at the coastal town of Dunkirk near the border of France and Belgium. In the past few days, the British Expeditionary Force had gone from being on the attack to being ordered to retreat to Dunkirk – and were now gathering there in their thousands, along with French and allied soldiers, and many refugees, awaiting rescue from the jetty (or mole) in Dunkirk harbour, and the beaches and sand dunes surrounding the coastal town. Surrounded and under heavy bombardment by the invading army and Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany, they were in a very tight corner, as one of their highest commanders put it, or a desperate situation, as one of the retreating soldiers observed.

Meanwhile at home, Operation Dynamo – the rescue plan – was flung together with as much speed as possible. The ambitious scheme was that British Naval vessels, hospital ships, destroyers, gunboats, trawlers and minesweepers were to get to the harbour at Dunkirk double-quick and lift the soldiers off to bring them home; Polish, French, Dutch and Belgian warships, trawlers, barges and launches were also to be involved. Churchill hoped that with luck, as many as 20,000 – maybe even 30,000 men could be rescued.

But the beaches, the shipping lanes, and approach routes, and the harbour at Dunkirk were all under heavy bombardment, making embarkation from the long mole in the harbour (where the water was deep enough for the big ships) a dangerous business at best, as it concentrated the waiting men and the ships into a clear target for the bombers. Though the mole itself miraculously survived for the whole of the evacuation, it was already damaged, and the harbour very quickly became hazardously blocked with wrecks of bombed vessels, making docking alongside the mole increasingly difficult for the big ships throughout the evacuation.

In addition to the seemingly endless queue of waiting troops along the mole, enormous crowds of soldiers formed along the 15km of beaches and dunes to the east of the bombed town, queuing out into the sea. Somehow these stranded men must be ferried out to the waiting ships in deep water by shallow drafted boats that could get close in to the beaches – and a call went out in Britain for sea-worthy boats, small ships and vessels to be volunteered for the job (which would be manned by Naval servicemen) – or if not volunteered, the boats would be requisitioned. The response was immense: nearly a thousand ‘little ships’ went to the rescue, many crewed by their owners, in a roll call of honour that stretched from lifeboats, merchant ships, fishing vessels, and seaside pleasure craft to Thames tugs and the London fireboats, and included private yachts and motor boats, sailing boats and even some tiny rowing boats with no compass or navigation instruments.

Over nine days from 26th May to 4th June, these little ships and boats somehow crossed the dangerous channel and got themselves to Dunkirk, where they worked tirelessly with the Navy, picking up hundreds, thousands of men, a few at a time, from the beaches and shallow water, and ferrying them out to the big ships. Then each cramped vessel full of weary, often wounded men (and some dogs) would struggle back home, still under heavy bombardment, to Ramsgate, Margate, Dover and other ports on England’s south coast, unload their cargo of men, and often turn straight round to return for another load.

Many ships and boats were lost, large and small, and those that limped home counted themselves bloody lucky to get back at all. Between them, over nine days, they brought back a staggering total of 316,663 people, ten times the number that Churchill and his government had hoped to rescue in his wildest dreams. Together, in a hastily improvised armada, they brought most of the army home.

Eighty-odd years on, Dunkirk holds a special place in our national consciousness. It’s perhaps the event of the Second World War that has particularly caught the British imagination and still moves us deeply – maybe because it appeals to our best ideas of nationhood, of voluntary, spur-of-the-moment courage, of individual honour independent of the state, of all mucking-in together in a gloriously triumphant English muddle, of heroism on a small, amateur scale making an enormous difference.

What is it about Dunkirk 1940 that speaks so urgently to our times, eighty-odd years on?

In 2020 the Covid 19 pandemic, the gravest emergency to strike this country since the second world war, claimed many lives and tore a great rent in our economy; again and again it reminded us of Dunkirk. From from the selfless service of our NHS to the disorganised fumbling of our leaders; from the overwhelming response to a call for volunteers to the independent search for solutions of our universities, pharmaceutical and engineering firms; from individual acts of heroism to collective acts of compassion, we saw so many instances of the Dunkirk Spirit alive and well in Britain today.

The Dunkirk Project explores this great true drama, and the inevitable slippage between the official history and the thousands of individual stories that make up such a momentous shared event, by setting a mosaic of day-by-day stories from Dunkirk 1940 alongside a surreally large artwork:

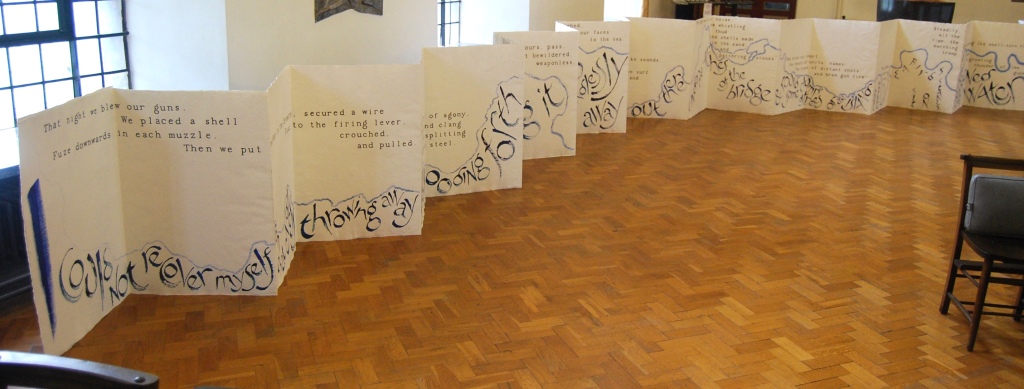

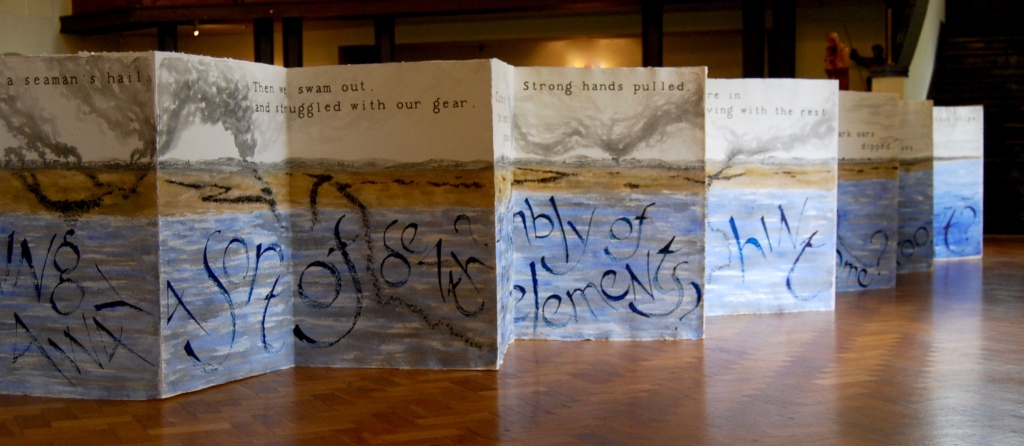

Thames to Dunkirk is an enormous artist’s book which opens up to a 17m-long free-standing paper sculpture. On one side is a watercolour map of the Thames, with the small boats that went to the rescue, and on the other side the great sweep of the Dunkirk beaches, where the waiting thousands stand, some up to their necks in the sea. Soldier-poet BG Bonallack tells the story of his experiences at Dunkirk, and below flows a questioning undercurrent by Virginia Woolf, in lines from The Waves. (More about BG Bonallack, Virginia Woolf and the making of Thames to Dunkirk here.)

Running alongside the huge book, the River of Stories brings daily news live on each of the nine days as the evacuation unfolds. This woven stream of memories, first hand accounts, poems and stories is open for you to add your own account, memory, family story, poem or comment, attaching it to the river, contributing to the continuing flow of the narrative, and our growing understanding of the event.

In thousands of visits to The Dunkirk Project since May 2010, many people have responded or contributed to the River of Stories, sharing individual unheard experiences and alternative views, as well as new poems and artworks. This has made The Dunkirk Project a valuable resource which combines first-hand accounts of a momentous event with a heightened awareness of its contemporary significance – including the difficult interface between individuality and communal responsibility that is reflected in any society’s myths – giving a wider, fuller, truer picture of this vast event which still has consequences for us all today. We need to hear these stories in order to be able to understand our own times more fully, and to be equipped to respond to the hazards, emergencies and issues of our contemporary world.

You can contribute by adding a comment directly to the stream, or send me your response by email to the.dunkirk.project[at]pottersyard.co.uk, so that I can weave it in.

The Dunkirk Project has been selected by the British Library for its UK Web Archive, and all contributions included will be preserved permanently in this archive as part of The Dunkirk Project. The archive is updated regularly in order to save successive versions of the websites and blogs it preserves. Thames to Dunkirk the artist’s book is now part of the British Library’s permanent collection, and can be accessed by readers; it was on show during 2012 as part of the British Library’s major exhibition for London 2012 Writing Britain, and has been digitised in a film.

Liz Mathews London, May 2023

Special features:

Thames to Dunkirk on film – an artist’s film takes a walk around the big book, in company with BG Bonallack and Virginia Woolf; and there’s a new article on the British Library’s blog.

Creating Dunkirk – artists’ views and visions – a new series of articles looking at artworks inspired by Dunkirk begins with a feature on John Craske’s astonishing embroidery The Evacuation of Dunkirk.

Creating Dunkirk 2 – The Withdrawal from Dunkirk by Richard Eurich – a visionary look at Dunkirk that takes in past, present and future.

Stranger than Fiction – highlighting extraordinary true stories from Dunkirk, including some surprising elements: twelve pairs of silk socks, a jam sandwich and a tattered postcard, and a treasured newspaper clipping showing one of the last soldiers to be evacuated from Dunkirk.

Heroic ships: 1 HMM Medway Queen – a series focusing on individual ships begins with a feature on the gallant paddle-steamer Medway Queen.

Heroic ships: 2 The Thomas Kirk Wright and the Poole Flotilla – a lifeboat, four ferryboats, fifteen fishing trawlers and a handful of pleasure boats on a mission.

This was Dunkirk – what was it really like, how does it look from here, and some parallels with our own times.

To River of Stories.

All text and photographs © Liz Mathews