4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk

On 4th June Dunkirk fell to the Germans.

(from Five Days in London, John Lukacs)

The signal ‘Operation Dynamo now completed’ circulated by the Admiralty on 4th June by no means implied that all BEF troops had been evacuated from France. There were still more than 100,000 British soldiers south of the River Somme; the British 51st Highland Division had to secure nineteen miles of the front line. ‘On this day alone 23 officers and over 500 other ranks were missing, wounded or killed. June 5th must have been the blackest day in the history of the battalion.’

(from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

It’s a complete mess. There are guns everywhere, as well as countless vehicles, corpses, wounded men and dead horses. The heat makes the whole place stink. Dunkirk itself has been completely destroyed. There are lots of fires burning. Amongst the prisoners are Frenchmen, and blacks, some of them not wearing uniforms, real villains, scum of the earth.

We move to Coxy de Bains by the beach. But we cannot swim because the water is full of oil from the sunk ships, and is also full of corpses. At midnight there is a thanksgiving ceremony on the beach, which we watch, while looking at the waves in the sea, and the flames in the distance, which show that Dunkirk is still burning.

(German staff officer who entered Dunkirk on 4th June 1940, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

The ‘miracle’ of the Dunkirk evacuation was well known to those who were alive in 1940. The accepted version is that all 338,226 members of the British Expeditionary Force were saved from the beaches near Dunkirk by the Royal Navy and an armada of ‘little ships’ who volunteered for the task. Churchill described the rescue of ‘every last man’ of the BEF as a ‘miracle of deliverance’. There is no doubt that these two groups performed magnificently, but, as with so many ‘miracles’, the story includes some myths. One was that only Royal Naval vessels and the ‘little ships’ were involved; the other that all of the BEF were evacuated.

In fact almost as many troops were left in France, most to be evacuated in the following three weeks by merchant ships. Certainly the Navy rescued the majority from Dunkirk and it fell to the various Admirals to organise all of the evacuations, but merchant ships carried more than 90,000 troops to safety. About three quarters of these were saved by railway steamers, ferries and excursions ships (generally described as ‘Packets’). The rest were carried by cargo vessels, coasters, tugs and barges. A further 5,548 stretcher cases were moved by other railway steamers acting as hospital carriers. In addition the Navy operated Dutch schuyts and British paddle steamers; these last still manned by their peacetime crews and civilian volunteers.

(Roy V. Martin, from Ebb and Flow: Evacuations and Landings by Merchantmen in World War Two)

The little boats all summoned again, as if to fetch off more troops. 20,000 of our men cut off.

(Virginia Woolf’s diary for 12th and 13th June 1940)

Some French soldiers were lifted from Dunkirk harbour during the next midnight, by French and English ships, the last ship (the Princess Maud) leaving at 1.50am on the 4th. As she left, a shell fell in the berth she had occupied a moment before. Though the lifting was finished, some useful cruising was done later, to pick up stragglers. The RAF and a number of motor-boats cruised over the Channel, and helped to find and save men wrecked in a transport and a barge.

On the evening of June 12th, some survivors were seen by a British aeroplane, who reported them to the patrols; a motor-boat went out at once and brought them off. These must have been among the last to be saved. The numbers lifted and brought to England from Dunkirk alone during the operation were: British 186,587; French 123,095 and those brought by hospital ships etc 6,981, making a total of 316,663.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder)

On the beaches and in the dunes north of Dunkirk, thousands of light and heavy weapons lay on the sands, along with munitions crates, field kitchens, scatttered cans of rations and innumerable wrecks of British army trucks.

‘Damn!’ I exclaimed to Erwin. ‘The entire British Army went under here!’

Erwin shook his head vigorously. ‘On the contrary! A miracle took place here! If the German tanks and Stukas and navy had managed to surround the British here, shooting most of them, and taking the rest prisoner, then England wouldn’t have any trained soldiers left. Instead the British seem to have rescued them all – and a lot of Frenchmen too. Adolf can say goodbye to his Blitzkreig against England.’

(Bernt Engelman, Luftwaffe pilot, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Philip Newman, the surgeon who we left yesterday at the Chateau, was captured by the Germans along with the wounded at the Chateau. In January 1942 he escaped for the second time (he had been recaptured after his first escape) and made it back to England. Later he became one of Britain’s leading orthopaedic surgeons and in 1962 he operated on Churchill, who had broken his hip. He was finally honoured in 1976, when he was appointed CBE.

(from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

‘When a week ago I asked the House to fix this afternoon for a statement, I feared it would be my hard lot to announce from this box the greatest military disaster in our long history.

I thought, and some good judges agreed with me, that perhaps from 20,000 to 30,000 men might be re-embarked, but it certainly seemed that the whole of the French First Army and the whole of the British Expeditionary Force north of Amiens and the Abbeville gap would be broken up in the field or else have to capitulate for lack of food and ammunition.

This was the hard and heavy tidings for which I called on the House and the nation to prepare themselves a week ago.’

(Winston Churchill, House of Commons 4th June 1940, quoted by AD Divine in his Dunkirk – who adds with restrained pride the following conclusion:)

Not 20,000 men but 337,131 came safe to the ports of England.

Tuesday 4th June News this evening of Mr Churchill’s speech in the Commons. He said he had thought it would have been his duty to disclose to the public the biggest military defeat we had ever suffered. Instead, 335,000 men had been saved and 50,000 lost, besides a lot of equipment. Although it had been a wonderful thing, we were not to look upon it as a victory – wars were not won by evacuations. It was indeed a wonderful speech, and even the BBC announcer got all het up about it.

(Doris Melling, from Our Longest Days: A People’s History of the Second World War, By the writers of Mass Observation, ed. Sandra Koa Wing)

The first attempt to rescue those left behind was named Operation Cycle: this was hampered by fog, the lack of ships’ wirelesses and heavy shelling. The evacuation ‘fell far short of Admiral James’s early hopes’. About 8,000 men of the 51st Highland Division were cut off and ordered to surrender; but by 13 June over 15,000 other troops had been saved.

Reinforcements were sent through St Malo; two thirds didn’t get beyond the port before they were recalled; wits in Southampton said that BEF meant ‘back every Friday’

Operation Aerial began on 15 June when 133 ships were sent to Breton ports; most of the 140,000 British troops were saved then. These vessels also mounted an evacuation of the Channel Islands. On 17 June the British liner Lancastria was sunk off St Nazaire.

(Roy Martin, from After Dynamo, May 2015 for The Dunkirk Project; his story continues later on this page.)

Roughly four o’clock in the afternoon the sirens went again. There was an instant attack, a terrific bang and blast which blew me off my feet – straight into the lap of an army officer. Another bomb went off and the ship lurched and started heeling over. Another bomb went off. Machinery like trucks, guns, stuff that was on the deck – human beings all hurtled down into the rails of the ship, into the water.

One of my most vivid pictures is of the big masts running parallel to the water, and people running along this and jumping off. I saw a rope and grabbed it. I couldn’t swim so I had to get hold of something that would keep me afloat. I grabbed an oar between my legs and a kitbag under each arm and just floated there.

(Sergeant Peter Vinicombe, Wireless operator, 98 Squadron RAF, aboard Lancastria, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

At least 2,710 people drowned, making this Britain’s worst maritime disaster.

(Roy Martin, After Dynamo, continuing below)

We were practically the last to embark on the Lancastria. By this time, she had round about 6,000 troops and air force on board. We were assigned to palliasses right on the bottom of the hold. It was pretty grim and, having a strong sense of self-preservation, I thought, ‘Well, on the trip home, if we get attacked by submarines or hit a mine, we wouldn’t have a chance down there – particularly if the lights have all gone.’ So I decided to stay on the top deck.

When she was hit I went to the bow to have a look back, and she was sinking slowly in the water. So I said to this chap, ‘Well, I’m a swimmer. I’m over the side.’ I just looked down about a thirty foot drop, took my tin helmet off, my uniform, my boots, clutched my paybook and my French francs and jumped over the side.

When I broke surface I swam about a hundred yards and came across a plank, which looked as if it had been blown off one of the hatches. So I sat on that, and the thing that surprised me was how calm I felt. I thought, ‘Well, I’ll sit on this. You’ll never see anything like this again.’ Fifty yards away from me, men were singing ‘Roll out the barrel’.

(Corporal Donald Draycott, Fitter, 98 Squadron, aboard the Lancastria, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

The sinking of the Lancastria was the subject of a BBC documentary and a page on the BBC History site tells the story in full with some moving images. Click here for a link to the archived page.

It’s something that you look back on with astonishment – that from the little trawler which picked us up, we were able to watch the final lurching and sinking of the Lancastria. She overturned completely in the end, so you could see the propellors, and even then you could see men standing on her upturned bows, afraid to jump into the sea. That was a pretty awful sight to behold. That was awful.

(Private William Tilley, Clerk, Royal Army Service Corps, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

After the rescues from Breton ports and the evacuation of the Channel Islands, the ships moved to Bordeaux, where much treasure was also saved. They then went on to St Jean de Luz, near the Spanish border. Embarkations only ceased when the Armistice came into force on 25 June. More of those rescued from these ports were Polish and Czech troops and civilians. The Polish liners Batory and Sobeiski embarked their countrymen and British cargo ships saved many more.

Further British and Allied troops and civilians were lifted from southern France. Voyages from western France took days, rather than hours, those from the south took weeks to reach the UK.

During the three operations the Royal Navy sent 102 ships and 45 requisitioned Dutch coasters. The Merchant Navies, mainly the British, provided 129 passenger ships and 141 cargo ships – an awesome response.

(Roy Martin, from After Dynamo. More from Roy Martin in today’s comments, including an account from Miss R Andrews who was rescued by the Ettrick, one of the last passenger ships to leave St Jean de Luz.)

Just then (it was almost midnight), we had our first taste of the kindness of a great people; ladies of the British Red Cross (I had no idea who warned them, or who had even thought of warning them) went from one compartment to the other with hot tea and pieces of delicious freshly made cake. What a luxury after the stale bread we had eaten for the last five days. We even received some warm milk for the children. My wife and the nurse could not restrain their tears. I also saw tears in the eyes of the Red Cross volunteer, a very kind and distinguished-looking lady with white hair, who was helping us. We were far from the Germans. That cup of tea and piece of cake had comforted us morally as well as physically.

(Paul Timbal, among those evacuated from Bordeaux on the Broompark on 19th June 1940, part of Operation Aerial. Timbal’s story is told in The Suffolk Golding Mission by Roy V. Martin)

Photo from archive of Polish Institute & Sikorski Museum in London, contributed by Roy Martin

It is said that many thousands – it is even said that four-fifths of them – have got back. A few days ago one thought they must either surrender or die. They have fought their way out in the greatest, strangest rearguard action ever known. Corunna, when one thinks how much fiercer and crueller war is today, cannot compare with it. However, it is a victory over adversity, not over Germans; it is a moral, not a physical victory.

(Sarah Gertrude Millin, 1 June 1940, from World Blackout.)

General Bernard Law Montgomery criticised the shoulder ribbons issued to the troops, marked ‘Dunkirk’. They were not ‘heroes’. If it was not understood that the army suffered a defeat at Dunkirk, then our island home was now in grave danger. Churchill saw things in much the same way: ‘Wars are not won by evacuations.’

(from Five Days in London by John Lukacs)

In retrospect, it was Dunkirk that lost Germany the war, because it suddenly brought Britain to her senses – made us realise that, with all our allies surrendered to the enemy, we alone had to carry the fight. The rest is history.

(Arthur Addis, Ammunition Officer, HQ, Third Division, BEF, quoted from the BBC website archive of the Dunkirk Evacuation by kind permission of his wife.)

No British soldiers were left on the beach and it is remembered as a success rather than a retreat – ‘snatching glory out of defeat’.

(The entry for ‘Dunkirk’ in the Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1991)

I, like so many others had taken for granted the history of England, of which Nelson was a part. And I knew that I, too, should in future feel a sense of responsibility.

(Second Officer Nancy Spain, WRNS, from Voices from the War at Sea, ed. John Winton)

FROM HIS MAJESTY THE KING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND MINISTER OF DEFENCE, 4th JUNE 1940, Buckingham Palace.

I wish to express my admiration of the outstanding skill and bravery shown by the three Services and the Merchant Navy in the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Northern France. So difficult an operation was only made possible by brilliant leadership and an indomitable spirit among all ranks of the Force. The measure of its success – greater than we had dared to hope – was due to the unfailing support of the Royal Air Force and, in the final stages, the tireless efforts of naval units of every kind.

While we acclaim this great feat, in which our French Allies too have played so noble a part, we think with heartfelt sympathy of the loss and sufferings of those brave men whose self-sacrifice has turned disaster into triumph.

GEORGE R.I. (Letter quoted in AD Divine’s Dunkirk, Appendix A; Appendix B contains the official list of the hundreds of ships, boats and other craft which took part in Operation Dynamo, and Appendix C lists 36 pages of Dunkirk Honours and Awards)

A brutal, desperate adventure forced on us by the most dire disaster.

(AD Divine, from Dunkirk. Divine went to Dunkirk on board the White Wing with Rear Admiral Taylor and was awarded the DSM)

This morning I lingered over my breakfast, reading and re-reading the accounts of the Dunkirk evacuation. I felt as if deep inside me there was a harp that vibrated and sang, like the feeling of seeing suddenly a big bed of clear, thin red poppies in all their brave splendour. I forgot I was a middle-aged woman who often got up tired and also had backache; somehow I felt everything to be worthwhile, and I felt glad I was of the same race as the rescuers and rescued.

(5th June 1940 diary entry in Nella Last’s War: A Mother’s Diary, quoted in John Lukacs’ Five Days in London)

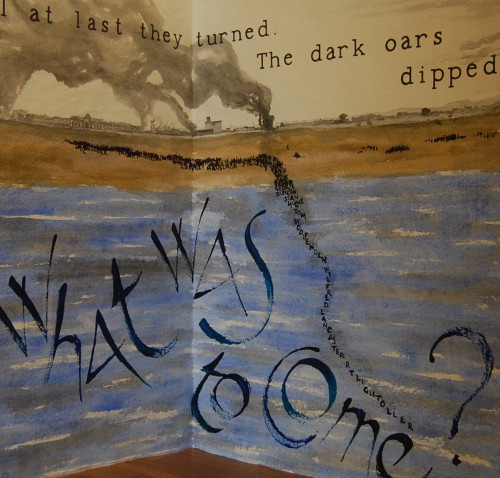

The little ships, the unforgotten Homeric catalogue

of Mary Jane and Peggy IV, of Folkestone Belle,

Billy Boy, and Ethel Maud, of Lady Haig and Skylark,

the little ships of England brought the Army home.

(Philip Guedalla, 1941)

On Sunday morning news came over the radio – Britain had declared war on Germany. What I feared more than my own death, war raged by everyone against everyone else, had been unleashed for the second time. Once again I walked down to the city of Bath for a last look at peace. It lay quiet in the noonday sunlight and seemed just the same as ever. People went their usual way, walking with their usual gait. They were in no haste, they did not gather together in excited talk, and for a moment I wondered: ‘Don’t they know what has happened yet?’ But they were English, they were used to concealing their feelings. They didn’t need drums and banners, noise and music, to fortify them in their tough and unemotional resolution.

I knew what war meant, and as I looked at the crowded, shining shops I saw a sudden vision of the shops I had seen in 1918, cleared of their goods, cleaned out, I saw, as if in a waking dream, the long lines of careworn women waiting outside food shops, the grieving mothers, the wounded and crippled men, all the mighty horrors of the past come back to haunt me like a ghost in the radiant midday light.

I remembered our old soldiers, weary and ragged, coming away from the battlefield; my heart, beating fast, felt all of that past war in the war that was beginning today. And I knew that yet again all the past was over, all achievements were as nothing – our own native Europe, for which we had lived, was destroyed and the destruction would last long after our own lives. Something else was beginning, a new time, and who knew how many hells and purgatories we still had to go through to reach it?

The sunlight was full and strong. As I walked home, I suddenly saw my own shadow going ahead of me, just as I had seen the shadow of the last war behind this one. That shadow had never left me all this time, it lay over my mind day and night. Perhaps its dark outline lies over the pages of this book. But in the last resort, every shadow is also the child of light, and only those who have known the light and the dark, have seen war and peace, rise and fall, have truly lived their lives.

(The closing paragraphs of The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig, first published in German in 1942, translated by Anthea Bell and published by Pushkin Press in 2009.)

Comments

Words in Company 4th June 2010

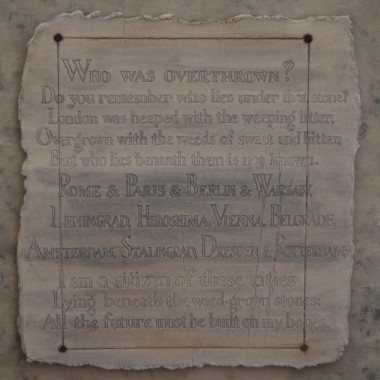

This collection of individual voices and responses (from then and now) emphasises the diversity of the people who were involved. A nostalgic view of Britain’s ‘finest hour’ can give an odd impression of uniformity, as though all the variations of political belief, religion, class background, race, gender, sexuality, had suddenly vanished. But involved in Dunkirk were Fascists, Pacifists, Communists (and no doubt every shade of political opinion in between), many different nationalities and races, many different religions – including of course Judaism – or none, the whole range of classes (when class divisions were absolute), social outsiders of every conceivable kind – among them the gay people whose war-time experiences are now coming out – and women, still second-class citizens despite their essential contribution to the war effort.

The united resistance to Nazism, the co-operative effort of Dunkirk, made by so many diverse kinds of people seems more extraordinary and courageous than mere unthinking obedience by a passive population. All these stories reclaim the Dunkirk myth for the individuals involved, they become separate beings again, not an army of nameless soldiers whose deaths are represented by numbers, or anonymous women nursing the wounded, but people with personalities, real lives of their own, strong voices.

The Dunkirk Project 4th June 2023

Nella Last was one of the Mass Observation diarists whose indefatigable wartime reporting has left such a matchless record of the Second World War as seen through civilian eyes. Her response to Churchill’s speech echoes some of Vera Brittain’s concerns:

Tuesday 4th June. We all listened to the news and the account of the Prime Minister’s speech and all felt grave and rather sad about things unsaid rather than said. Sometimes I get caught up in a kind of puzzled wonder at things and think of all the work and effort and unlimited money that is used today to destroy, and not so long ago there was no money or work and it seems so wrong somehow, feeling there was a twist to life when money and effort would always be found to pull down and destroy rather than build up.

From Our Longest Days: A People’s History of the Second World War, By the writers of Mass Observation, ed. Sandra Koa Wing

The Dunkirk Project 4th June 2010

Vizzer on the BBC history message board conversation about The Dunkirk Project asked:

‘Does anyone know what role was played by the Czechoslovak forces at Dunkirk? By the prominent number of Czech flags at the commemorations, it must have been considerable.

————

Tricetarops in reply 4th June 2010

The Czech presence would be about the Liberation of Dunkirk. The Czech Brigade was attached to the Canadian Army and was part of the force besieging Dunkirk 1944-45. The German army surrendered to General Liska in May 1945.

—————–

Roy Martin also in reply to Vizzer 26th September 2010

Troops and civilians continued to be lifted from ports in the west and south of France until 25 June 1940. Most of the rescues were carried out by merchant ships, ranging from Ocean Liners to little coal boats. In all about a quarter of a million people were saved after Dunkirk. Among them were many Polish and Czech citizens.

I have written a book that includes several chapters about the part played by merchant ships in the rescues from France and would be happy to provide more information if required.

The Dunkirk Project 4th June 2010

We last heard from Lt. Wilkinson RAMC (whose story we’ve followed since he was sent out to Dunkirk on 26th May with four other medical officers) on the morning of June 3rd arriving back in Dover. By 4th June 1940 he’d finally reached home, where he recorded his experiences in a notebook – the last entry being on June 5th:

June 5th

The five medical officers returned to Castleman’s where a special celebration was held, so much so that George gradually became quite inarticulate and finally retired gracefully to bed.

(Many thanks to George Wilkinson for contributing his father’s story.)

Liz Mathews 4th June 2010

The artist Stella Bowen, writing in July 1940, expressed this unity of resistance by multifarious individuals vividly in her book ‘Drawn from Life’:

Events are forcing everyone to examine the roots of their security and the charter of their citizenship. Now that the storm is here, it does not seem to matter much whether one used to be called a ‘flabby liberal’ or a ‘dirty red’. It does not matter whether one was a diligent wage-earner with an insurance policy and a hire-purchase home, or a thriftless artist who did as he liked and lived on luck and charity, for now we are all swimming for our lives in the same stormy waters. We continue to fight for our existence. And we are getting nicer all the time, so that even a poor stuck-up painter can feel sisterly towards football-fans and people who eat prunes and tapioca. Surely this is an improvement!

Stella Bowen’s daughter Julia Loewe wrote in 1984 about her mother:

She was basically apolitical, though her heart was in the right place. (Who can doubt now, that it was right to be a pacifist in the First World War, and equally right to wish to fight the Nazis in the Second?)

Liz Mathews 4th June 2023

More on pacifism – from Sybille Bedford

Plans aimed towards return. England. For the duration. When Germany invaded Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, and in mid-May France, we were still dithering in the South of France. German armies marching, advancing… Did I then still feel in terms of the horrors of war? I could not get them out of my mind where they clashed with the urging desire that this war must be won. Which meant fought. The recurrent dilemma of the pacifist.

Now we had to think of flight. Our own. Allanah and I got to Genoa, where we spent some fraught days slinking about… waiting… until allowed at almost the last hour to board an American passenger ship. The voyage took some twenty days. On each, the telegraph brought dire news – Petain’s speech asking for an Armistice… France signing an Armistice… Britain alone holding out.

Were we at the beginning of the end of life as we had known it?

Sybille Bedford, from Quicksands Penguin 2005

The Dunkirk Project 4th June 2023

As soon as the evacuation from Dunkirk was over, through all the turmoil of the Fall of France and the Armistice of 25th June, the threat of invasion was at its height in Britain. Had we not managed to retrieve the largest part of our fighting force from Dunkirk, that threat would have been impossible to stave off. As it was, our arms and military capacity had been severely curtailed by the terrible loss of arms, equipment, ships and lives during the withdrawal. Before the Battle of Britain changed the course of the war in August 1940, and before the Blitz, the threat of invasion was imminent:

Muriel Green, 1940:

Tuesday 14th. Woke up at five. Laid in bed and heard the men go to work at the shingle quarry. I was not listening but overheard the work ‘parachutes’ by two workmen. The next two a few minutes later were also talking of invasion of England. Everybody round here had it in their minds about what we shall do if invaded. Most people seem to expect it. Most have very wild ideas about what we ought to do.

Why have we not had instructions? Why not a public Information leaflet on the subject along with other wartime instructions we have had? Ever since the war started not a word to the civil population on what to do on enemy invasion. I wonder if the government has any plans. Everyone here is wondering if we stay put or hop it if they land. Some think both ways. We keep debating the subject of fleeing or remaining, and do not know whether to pack a case as some people have or not. We have had our handbags ready with bank books in since the day war was declared.

Muriel Green, 1940, from Our Longest Days: A People’s History of the Second World War, by the writers of Mass Observation, ed. Sandra Koa Wing

———–

Stella Bowen, June 1940:

The other day, a knock at the door revealed two officers, too tall for the beams of our low parlour ceiling. They were excessively courteous and informed us that ‘”in the event of an emergency” (it seems you never say, “If the Germans come”), they would wish to commandeer our cottage as an army first aid post. It was solid, they said, and well off the road and they could easily lay twelve men on stretchers on the parlour floor. We might go or stay as we liked. If we stayed, we should have to live upstairs. If we had good nerves we might be useful…

Good nerves… How could we tell?

And now the air raids have begun. We put cotton wool in our ears, and hope to stay asleep when the sirens howl. If there are any bombs the cottage shakes and the windows rattle. The anti-aircraft goes wuff-wuff and the German planes fill the sky with a pulsating hum, like a swarm of evil bees.

I want to live through it. I want to see what happens. I want (vain hope!) not to be too frightened…

Stella Bowen did live through it, and died in 1947, at the age of fifty-two.

Stella Bowen Drawn from Life Collins 1941 Virago 1984

——————

Doris Melling:

Wednesday 5th June. Slowly but surely the British public is realising the predicament we are in.

Monday 24th June. Details of the humiliating armistice terms for the French – they have got to hand over everything, including the navy. Everyone very downcast. One woman this morning: ’Well, at least we know where we are now. We are not helping anyone but ourselves.’

Peace terms confirmed this evening. Listened to a major from the BEF on the wireless, telling how to overcome fear and take the best possible cover from dive bombers. We need more of this. If the public, and particularly the women, can stand up to air raids, it will be half the battle.

Friday 30th August. Well, well, well. We had the Biggest and Best air raid ever last night. It was amazing. I have never heard such a row going on in my life. Simply terrific. Felt very calm and not the least frightened. As each plane came over and dropped its bombs another one appeared. The wash house shook like the devil. Went on from 10.20 to 2.30 without a break. Smoked innumerable cigarettes and felt hungry.

About 3 o’clock the All Clear went. Could hear people getting home from the pictures. It really is no joke. I shan’t go to the second house pictures any more. Fell sound asleep.

On the way down to the office this morning everyone was looking out for damage. No morning newspapers. Felt rather excited, personally. That was a proper raid. I detest sitting in a shelter with nothing happening.

Doris Melling, from Our Longest Days A People’s History of the Second World War by the writers of Mass Observation, ed. Sandra Koa Wing Folio Society 2007

The Dunkirk Project 4th June 2010

On the Radio 3 message board conversation ‘Echoes of Dunkirk?’, comparing ‘the Dunkirk spirit’ with ‘the spirit of the Blitz’, a contributor asked for ‘any more stories?’

The only things my mum remembers about Dunkirk itself are the newspaper reports while it was happening – and these she remembers vividly, though she was only a child. But the Blitz – yes: my grandparents’ house was in Crayford (bomb alley) on the direct approach to London, and was destroyed by a doodlebug in the last year of the war. My mum (Joyce) climbed out of the rubble, and her younger sisters (Doreen and Sylvia) and her mother (Doris) were rescued – my grandma was severely wounded, though she saved baby Sylvia’s life. My grandfather (John) was out working as a stoker in a munitions factory, and came home to find it gone.

My grandma, just one of the ‘more civilians than combatants who were wounded and killed in the second world war’, spent several years in hospital, enduring repeated operations, and though she lived until the 1980s, her health, her relationship with her children, and her life were profoundly affected. My family still feels some of these effects today (how not?), though it’s not something that my mum likes to talk about much.

The past is a part of everybody’s present.

Liz Mathews

The Dunkirk Project 8th June 2010

More on the long-term effects of Dunkirk:

Mary contacted The Dunkirk Project to share on two stories of Dunkirk experiences.

Harold, a neighbour, talked often in the village of being left behind. One of the rearguard, he didn’t reach Dunkirk in time to be evacuated, was captured by the Germans immediately after Dunkirk fell, and force-marched across Europe to a prison camp in Poland, where he spent the rest of the war. His bitterness lasted for the rest of his life.

Alan, a painter from Somerset, was one of the rescuers; he took his own boat and succeeded in bringing several men home, but was so disturbed by what he had witnessed that for the rest of his life he painted almost nothing but images of Dunkirk and what he saw there.

Liz Mathews 27th August 2010

Vita Sackville West began work on her long poem The Garden in 1939, and continued work on it intermittently throughout the war. Towards the end, she wrote:

“This war will be over soon.”

Yes, in September or perhaps November,

With some full moon or gibbous moon,

A harvest moon or else a hunter’s moon

It will be over.

Not for the broken innocent villages,

Not for the broken innocent hearts:

For them it will not be over,

The memorable dread,

The lost home, the lost son, and the lost lover.

Under the rising sun, the waxing moon,

This war will be over soon,

But only for the dead.

———-

A response from Liz Mathews 4th June 2020

As Britain begins to move out of lockdown for the Covid-19 pandemic, I keep thinking of this poem, and feel that the last stanza quoted here has a special resonance today. In Britain we have got through the immediate impact of the virus, with a great scar running right across our country, our economy and our society. And we are as yet unable to assess the full consequences. Perhaps this is an event, like Dunkirk 1940, that is never truly over, but something with consequences we will have to live with and learn from.

Dunkirk, though it sprang from a disastrous circumstance, was ultimately something that brought us great strength and endurance, not least because it reassured us about our humanity, reminded us of our shared responsibility and compassion, and helped us re-discover the strength of a society peopled by courageous caring individuals. We must not allow it to be misappropriated as a symbol for division and civil conflict, when it was the greatest coming-together of people this country has known for centuries, people whose common humanitarian aim was to assist those in dire need – without checking their passports or credit cards first.

John Dibblee March 15th 2012

We left John Dibblee on 31st May, on the deck of a commercial vessel heading homewards, but his war experiences didn’t end there:

For the remainder of my war, I had the misfortune to be on the Dieppe Raid, again as forward OP for an elderly gunboat with single gun. As we disembarked, I knew my role was pointless, as the naval signalman’s radio could not get any signal from our ship. We did however manage to survive as many Canadians did not, albeit as prisoners of war. A reprisal of Hitler’s was to handcuff all Officers of the Raid in captivity. We sat out the War in an OFLAG near Kassel, before joining many of the forced marches retreating from the advancing Allies. After our guards finally fled, we were picked up by American troops and returned to the UK within 48 hours, a disorientating experience.

(Many thanks to Robin Dibblee for talking to his father John Dibblee about The Dunkirk Project, and contributing the his story.)

————–

Linda Rowley in response to John Dibblee 18th June 2013

My mother’s first husband was taken by the Germans at Dunkirk and died in a POW camp in Poland.

My mother’s first cousin was among the last soldiers to be rescued at Dunkirk, and lived to his 80’s.

Just the luck of the draw, I suppose.

——–

The Dunkirk Project in response to Linda Rowley

Linda Rowley added some more information to her relatives’ stories on yesterday’s page 3rd June 1940 – Towards the end. These sad stories give an insight into how the lasting consequences have resonated down the years.

Roy Martin 25th May 2015

Roy sends more on Polish and Czech forces at Dunkirk and in the subsequent evacuation operations:

A lady called Halina Macdonald first put me onto the photo shown on this page of SS Alderpool crowded with evacuees – some of her family were on the ship. (The source was the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London who gave me permission to use it in my books.) The ship ran out of food and water on the two-and-a-half-day trip. On arrival at Plymouth, the Admiralty decided that the ship should go on to Liverpool in that state; but the Master and the Captain of the escort refused and said that they were off to Falmouth. The Admiralty then relented and let them come into Plymouth.

There is another great Polish story from that time – how the Chorzow, a little Polish cargo ship, saved the Polish National Treasure and took it to Falmouth. From there it went to London/Glasgow and then the Batory took it to safety in Canada for the duration of the war. Another good account is how a young Czech student called Marianne Adler escaped from the south of France on a tramp steamer. Somerset Maugham was also rescued from there by the same mode of transport – he wrote about his experiences in Strictly Personal.

————-

The Dunkirk Project, in response to Roy Martin May 25th 2015

Many thanks to Roy Martin for the stories and photo on this page about these post-Dunkirk evacuation operations, and for sharing his expertise and great fund of stories with us. More information about Roy’s books can be found on his website at http://www.brookhousebooks.co.uk – his latest book is The Suffolk Golding Mission: A Considerable Service, which tells the astonishing story of the tramp steamer Broompark, among the 180 merchant ships that sailed from France in the three weeks after Dunkirk. Instead of the 500 evacuees that Captain Paulsen expected, he was introduced to two men who were intent on saving a valuable cargo and a number of scientists. The cargo included two crates of gem diamonds (even then valued at up to £3 million sterling), plus the Allies’ total supply of Deuterium Oxide, a nuclear moderator, as well as 600 tonnes of machine tools and many secret papers and plans. Roy Martin’s masterly handling of this exciting story adds another twist to the evacuation tale – another extraordinary happening that seems like the stuff of fiction but is all too true.

David Mitchell May 25th 2015

David Mitchell (a conscientious objector who served his 1950s National Service as a hospital orderly) has emailed The Dunkirk Project with his cousin’s story:

I was nine when Dunkirk happened and totally unaware, but my much older cousin Laurie was captured and spent the rest of the war in a stalag somewhere. He was married with two small children, but his elder child, a little boy called Peter whom I just remember, died while he was away in one of those ways children did then, and the marriage never recovered from this and from his absence; they divorced after the war.

(Our dear friend David died in 2020 of Covid. He was survived by his partner David Hass, and is sorely missed by so many friends. More about David M and David H on Stranger than Fiction.)

Jeremy Hooker June 4th 2015

I was born in an air-raid, and my first memory is of being taken down into an air-raid shelter in the garden. I was wrapped up in a utility blanket – the smell and feel always brings back that – lovingly handled – descent into the dark.

This is a wonderful project. True remembering is essential to our humanity.

Roy Martin July 2nd 2015

Roy Martin, who has told us so much about the evacuations from France after Dunkirk by merchant ships, sent this account of an Englishwoman rescued by one of the very last ships to sail from St Jean de Luz. I’ve quoted her story at length here because it’s such a vivid account of an ordinary person’s extraordinary experiences – and also shows what the merchant ships were up against in their valiant rescue operations:

In June 1940 Miss R Andrews was a nurse at the American Hospital in Paris (AHP) among several other English members of staff. Her story starts on 10th June:

‘Although the French authorities and even the military were still thinking Paris would never be taken, luckily the AHP considered the situation as it concerned us four English women who – if the Germans took Paris – would certainly be interned’

and they were lent the hospital director’s Buick to drive down to an AHP nursing home in Chateauroux, about 100 miles south of Paris, to ‘stay down there until the threat of an attack on Paris or the possibility of war on French soil had blown over’, apparently unaware of the whole Dunkirk scenario.

They set off on 10th June, just three days before the Germans marched in to Paris, ‘fully expecting to be back in Paris in a few weeks’, and began a journey that was

‘quite ghastly. Millions of Paris inhabitants all had the same idea and the roads were jammed with cars. It was very hot and soon everyone’s car engine began to boil as we edged along.’

By evening they had made it as far as Orleans, where they met a lot of

‘RAF personnel on their way to Brest to be picked up by the SS Lancastria. We learnt later that it had been bombed by the Germans with a loss of about 3,000 men.’

After many difficulties they arrived at Chateauroux on 12th June,

‘and found it chock full of refugees – soldiers retreating on their own, hundreds of cars, people of all nationalities, Belgian farmers with all their goods and chattels loaded onto creaking farm carts, men pushing bicycles with bulging luggage and usually a dog on the handle bars.’

There they learned that

‘the roads we had come along had been bombed by German Stukkas, and that France was to be partitioned, and all communication with Paris was henceforth cut. We knew then that there was no going back and that our future was quite uncertain – except that we had to get to England somehow, even if it meant going through Spain.’

After a week in Chateauroux, looking after refugees, ‘we decided to move on towards Bordeaux and the Spanish border, armed with blankets and a supply of tinned food and some money’, as well as the precious Buick full of petrol.

On the next stage of their journey they evaded ‘a strange phoney Englishman’, stopped briefly at the military hospital in Angouleme ‘full of French and Polish soldiers in wards and on corridors lying on mattresses on the floor’, learned of the fate of friends and relatives left behind in Paris and now interned for the duration, parted for ever with Miss Andrews’ little dog Vicky, ‘cried buckets’, and eventually realised how serious their situation was:

‘There was nothing we could do to help at the hospital. Everyone said that being English we must push on and get back to England if we didn’t want to spend years in an internment camp. So we went on to Bordeaux to find the British Consul and get advice. But the town was crowded with refugees and the Consulate was besieged by frantic Brits.’

They encountered ‘an adorable young man in Naval Uniform’ (Ian Fleming), apparently organising the evacuation of the entire British refugee population during one afternoon, who advised them of the imminent arrival of a Dutch liner they could sail with, and feeling confident of this outcome, they went shopping in Biarritz – and inevitably missed the liner. The next few days were spent hanging about, exploring Biarritz and going to the Consulate twice daily for news of ships. They were rewarded on 20th June with the news of a British liner due that day.

‘We were told to drive down to the quay and that we would have to abandon our cars. As ours belonged to the Director of the AHP we hoped to do better than that, so Kingie and I set off to see a rich American ex-patient and friend of the Director who lived near Biarritz.’

Of course they missed that liner too. (‘We were a bit dismayed…’)

‘However the next day it was announced that the very last boat would be coming in to St Jean de Luz near the Spanish border. So we made an effort and went off down there arriving in the late afternoon.’

After bravely risking a delicious meal of roast duck in ‘a famous restaurant there’, the four English women did at last manage to board the SS Ettrick, and were given a cabin to themselves by the English crew. Over the next two days before the ship sailed they were joined by ‘the remnants of the Polish army – all 600 of them’, as well as ‘King Zog of Albania with his sisters, his wife, his young baby, his retinue, his servants, his luggage, and his country’s state treasure in huge long metal coffins, one of which nearly fell in the water’. The Ettrick finally got under way on Monday 24th, crammed with evacuees and treasure, accompanied by the huge liner Arandora Star, also full to bursting, and escorted by two destroyers.

‘For five days we zig-zagged across the Bay of Biscay’

– eventually anchoring off Plymouth on Friday 28th June:

‘We were taken in ferry boats to the quayside where WVS women gave us bars of chocolate and a band played the Marseillaise. Well, that was the first time we really realised we were refugees in our own country and I for one burst into tears. Later, the lot of us repaired to a refreshment room in the station where we bought a bottle of whiskey – made us weep all the more. After an uncomfortable seven hour journey in the guard’s van of our train to London we arrived next morning, met at the station by a relative of one of our party who very kindly bought us a splendid English breakfast (food again!). That morning we learnt about Dunkirk.’

(Miss Andrews’ story extracted from her account in the IWM archive, ref 99/37/1. Many thanks to Roy Martin for sending the story to The Dunkirk Project.)

————-

Response from Roy Martin 2nd July 2015

Credit’s due to my daughter-in-law Claire and her daughter Ruby, who, armed only with rather vague details, found and copied this report, and another. Plus a December 1943 collection of photographs from the Tyneham area in south Dorset, showing the many buildings that had been hurriedly evacuated for D-Day training. The people, including members of our family, were never to return and most of the properties are ruined. Roy

Vivienne Menkes-Ivry 4th June 2020

Reading all these amazing stories, some of which mention Poles and Frenchmen and Belgians, made me wonder how many of the non-British servicemen who were rescued and ferried to Britain went on to join our own armed services as my Belgian father did. (I contributed a story about him to The Dunkirk Project – on page 1st June 1940 – Homeward). I know there were quite a lot of Polish pilots in the RAF, including I believe a whole Polish squadron, but I don’t know whether any of them had been evacuated from the French and Belgian beaches.

It may well be that the Armada of little ships made an even greater contribution than rescuing so many British troops in that men who would otherwise have been taken prisoner or worse were able instead to contribute to the British war effort.

Vivienne Menkes-Ivry

—————–

Liz Mathews in response to Vivienne 4th June 2020

Thank you for this, Vivienne – a very good point. I’ve copied your comment from a post into this conversation about Czech, Polish, French and Belgian evacuees from Dunkirk, many of whom were troops and some refugees, and I will see if I can get any further information about this link between the Evacuation and the services; it surely must be the case that many of those who later joined our armed services as your father did, had in fact been evacuated from Dunkirk – or possibly from the subsequent evacuation operations mentioned by Roy Martin above on this page; he speaks of 163,000 more troops being brought back from the Breton ports, and then the evacuations from Bordeaux and St Jean de Luz bringing back Polish and Czech troops and civilians as well as British troops and medical workers. A remarkable thought, considering the European nature of the rescue operation, which involved British, French, Dutch, Belgian and Polish warships, trawlers, patrol craft, launches, drifters, and eel boats, to name but a few.

Liz Mathews, for The Dunkirk Project

Christopher Hughes 5th February 2021

The Peggy IV mentioned earlier was sailed by my dad, Stan “Squibbo” Hughes who worked as the boy on Thames barges. He was 17 at the time and as he came close to the shore the boat was hit by a bomb and sank. His next memory was of a soldier feeding him brandy to resuscitate him! He remained a boatman all his life and never did learn to swim.

————-

(More details about Squibbo Hughes’ narrow shave on Stranger than Fiction.)

Please add your own comment or response into the comment box below

or email the.dunkirk.project[at]pottersyard.co.uk

Leave a comment