27th May 1940 – An extraordinary armada

The Admiralty have made an Order requesting all owners of self-propelled pleasure craft between 30′ and 100′ in length to send all particulars to the Admiralty within 14 days from today if they have not already been offered or requisitioned.

(BBC announcement on 24th May 1940)

Mr Douglas Tough of Tough Brothers Ferry Road Boatyard in Teddington was authorised by the Admiralty to requisition and collect boats from the Thames. ‘Fortunately the boats were there, in muddy estuaries and creeks, in deserted moorings along the coasts of Kent and Sussex and in the quiet reaches of the Thames.’

He and Ron Lenthall collected more than 100 boats from the upper Thames, towed them to Sheerness, fuelled them and collected them together at Ramsgate, where naval officers, ratings and experienced volunteers were put on board and ‘directed’ to Dunkirk. Some of the owners were less than pleased, many others immediately volunteered to take their own boats.

(Information from IWM archive and David Divine’s Dunkirk)

I think there were more than a thousand craft in all. I myself know of fishermen who never registered, waited for no orders, but, all unofficial, went and brought back soldiers. Quietly, like that.

(David Divine, Miracle at Dunkirk. David Divine went to Dunkirk on board White Wing with Rear Admiral Taylor.)

Basil Smith, a doctor from London, had registered his motor yacht Constant Nymph early, and immediately volunteered to take his boat, with a crew of two young ratings; but the issue of permits and other red tape caused frustrating delays, and he didn’t arrive at Dunkirk until dusk on 30th May.

(story from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

Dunkirk was just like Picadilly Circus.

(Captain of Ryegate II, a motor-yacht from Tilbury)

Many of the ships pressed into service had to be fitted with instruments; they had not even adjusted compasses. The work, and the organisation of the work, had to proceed together. At one time there were as many as a hundred and fifty craft anchored outside Dover Harbour, while another fifty waited in the Downs for orders and supplies. Knowing some of the difficulties, I should say that the Operation was the greatest thing this nation has ever done.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder)

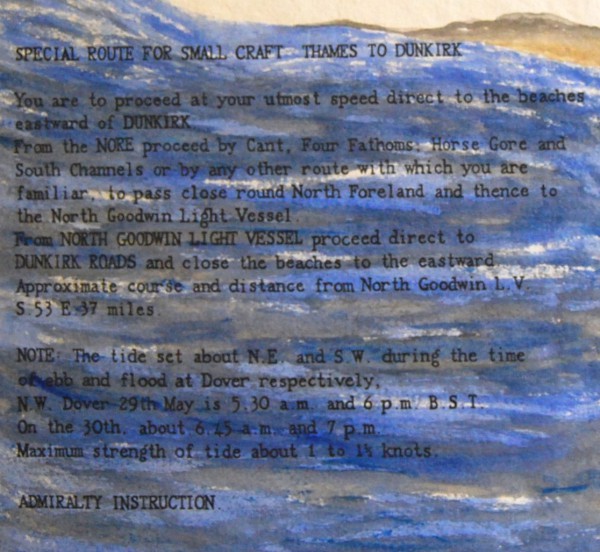

SPECIAL ROUTE FOR SMALL CRAFT THAMES TO DUNKIRK

You are to proceed at your utmost speed direct to the beaches eastward of DUNKIRK. From the NORE proceed by Cant, Four Fathoms, Horse Gore and South Channels, or by any other route with which you are familiar, to pass close round North Foreland and thence to the North Goodwin Light Vessel. From NORTH GOODWIN LIGHT VESSEL proceed direct to DUNKIRK ROADS and close the beaches to the eastward. Approximate course and distance from North Goodwin L.V. S 53 E 37 miles.

NOTE: The tide set about NE and SW during the time of ebb and flood at Dover respectively, NW Dover 29th May is 5.30am and 6pm BST. On the 30th, about 6.45am and 7pm. Maximum strength of tide about 1 to 1½ knots.

ADMIRALTY INSTRUCTION

The first assembly was typical of the whole of this miniature armada. A dozen or so motor yachts from 20 to 50 feet in length, nicely equipped and smartly maintained by proud individual owners, a cluster of cheap ‘conversion jobs’ mainly the work of amateur craftsmen who had set to work in their spare time to convert a ship’s lifeboat or any old half discarded hull into a cabin cruiser of sorts and half a dozen Thames river launches resembling nothing so much as the upper decks of elongated motor buses with their rows of slatted seats, but given a tang of the waterside by rows of painted lifebuoys slung around the upper sails. The very names of these latter craft are redolent of the quiet of Richmond, Teddington and Hampton Court: Skylark, Elizabeth and Queen Boadicea. A strange flotilla indeed to be taking an active part in what has been described as the greatest naval epic in history.

(Lt. Dann, a naval officer who went with the first convoy of small boats to Dunkirk, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

Now from every port the boats were moving out, bent on a crazy incredible rescue from Ramsgate and Margate, from Dover, Folkestone and Portsmouth, from Sheerness and down the tidal rivers, a fleet almost a thousand strong. There never had been an armada like it. The destroyer Harvester, built to fulfil a foreign contract with all its instructions in Brazilian; the Count Dracula, launch of a German Admiral, scuttled at Scapa Flow in 1919 but salvaged years later; the armed yacht Grive, where the captain, the Hon Lionel Lambert, took his own personal chef; the Canterbury, the bejewelled ferry-boat of the cross-Channel run; Arthur Dench’s Letitia, the little green cockle boat from the Essex mudflats; the Thames hopper barge Galleon’s Reach; Tom Sopwith’s yacht Endeavour; the Fleetwood fishing trawler Jacinta, reeking of cod; the Yangtse gun-boat Mosquito bristling with armament to ward off Chinese river pirates; Reiger, a Dutch schuit, redolent of onions, still hung with geranium pots; the Deal boat Dumpling, built in Napoleon’s time, with a skipper seventy years young. On the bridge of the destroyer Malcolm, the navigating officer Lt. Ian Cox was moved almost to tears the see the oncoming fleet led by, of all craft, the Wootton, the old Isle of Wight car-ferry, wallowing like a sawn-off landing stage through the water.

(Richard Collier, from The War at Sea ed. John Winton)

One of the first small ships to go was Advance, a motor launch owned by Colin Dick, who was a member of Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts (and he had bought Advance from the British Union of Fascists). His affiliation didn’t prevent him from volunteering to take his boat to the rescue. ‘An officer came down to the jetty, and told us what we were wanted to do, that it would be very dangerous, but it was very important, and that we should have ample support from the RAF.’

They set off with a convoy of small boats, finding their way by the great pall of smoke from the burning town and oil stores. On the way they were machine-gunned by German planes – the Advance was damaged, but they pressed on. Once at Dunkirk, they began to ferry soldiers from the beaches out to the destroyers, whose depth of draft didn’t allow them to get further inshore, and spent a harrowing time under bombardment, rescuing men from the water, and narrowly avoiding disaster. They only returned to Ramsgate when their fuel ran out.

(Story from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

On the way in to the beaches, our captain hailed a ship that was coming out with troops and said, ‘How many are there there?’ The reply that he got back was, ‘There’s bloody thousands!’ There was no order on the first occasion at all. It was more or less a free-for-all. Soldiers don’t know the life-saving capacity of boats. We could only take ten to twelve in a whaler to ferry out to the naval ships, and so we kept our distance from the water’s edge; it was no good us going right up on the beach, because we’d got to get seaborne again.

(Coxswain Thomas King, aboard HMS Sharpshooter, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices. More from Thomas King tomorrow, 28th May)

The evacuation of the beaches was a magnificent bit of organisation but it has gone down in history that the whole of the BEF came off Dunkirk beaches which is nonsense. Thirty to forty thousand men were evacuated from the beaches by the ‘little ships’ which was a magnificent effort. It was however, a drop in the ocean compared to the evacuation, by the Royal and Merchant Navy from the jetty, of some 220,000 men.

(Lt. Bruce Junor, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

We arrived at Dunquerque with five other ships during a very heavy air raid. I decided to go in. I went alongside the wall and took off 900 troops, many of them wounded; we were subjected to heavy gunfire all the time, but not much bombing. I returned to Dover and landed the troops.

(Captain G Johnson of the Royal Daffodil. More from the Royal Daffodil every day until 2nd June)

There was a little dog, a terrier-type mongrel, who came on board with some of the soldiers. He only understood French. When I spoke to him he wouldn’t leave me. That little dog came back with us on the other two trips that we made. He didn’t understand any English, which rather tickled some of the soldiers.

After Dunkirk was all over, Kirk was collected by a PDSA van to go into quarantine for six months before he was taken on to the staff of the parish where our sub-lieutenant’s father was vicar. All of us cheered the old dog off. It was a very nice human touch amongst all that carnage of Dunkirk – as though people, in spite of all, were still caring.

(Ordinary Seaman Stanley Allen, aboard HMS Windsor, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices. 170 dogs were evacuated with the soldiers – information from the Imperial War Museum archive.)

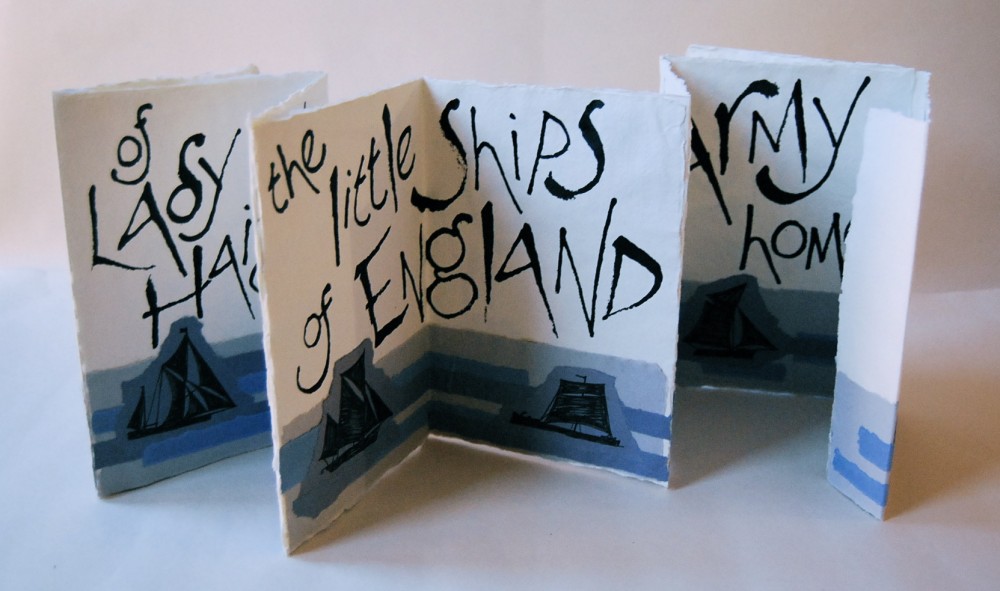

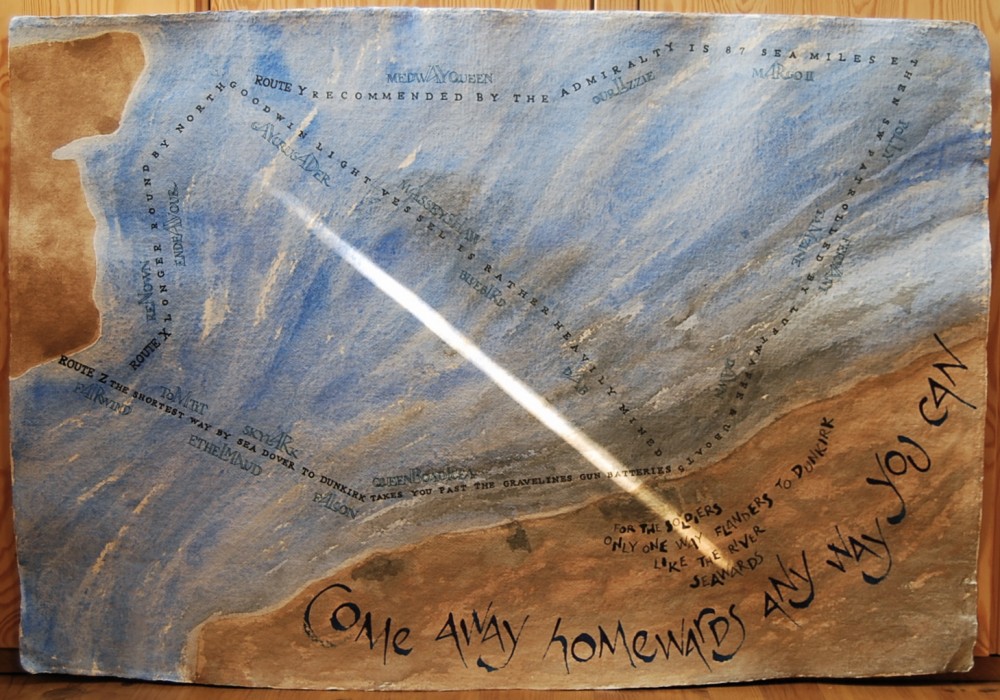

Four Dunkirk Roads

Route Z, the shortest way by sea

Dover to Dunkirk, takes you past

the Gravelines gun battery.

Tom Tit, Skylark, Queen Boadicea

Ethel Maud, Fairwind and Falcon

Route X, longer,

round by North Goodwin Light Vessel

is rather heavily mined.

Renown, Endeavour, Gay Crusader

Massey Shaw, Bluebird and Dab

Route Y, recommended by the Admiralty,

is 87 sea miles E then SW

patrolled by Luftwaffe and U boats.

Medway Queen, Our Lizzie, Margo II

Polly, Tamzine, Fervant and Dawn

For the soldiers, only one way

Flanders to Dunkirk –

like the river, seawards.

Come away homewards

any way you can.

(Liz Mathews)

Comments

The Dunkirk Project 27th May 2010

Grumpyfred wrote to The Dunkirk Project on the BBC website history messageboard with this story:

My late father went the wrong way during the Dunkirk evacuation. He was a Royal Marine, still under training, when he was dragged out of camp and stuck on a boat to assist. The first my mother knew about it was when he arrived home on survivors leave, his ship having been sunk under him. He then took part in every major landing and advance from North Africa to Normandy.

Words in Company 27th May 2010

This project is such a clear example of the contemporary idea of history as not a fixed monolith of established fact, but a shifting, many-faceted mosaic of individual experiences with different perspectives and interpretations, which sometimes seem contradictory in detail, but combine into a far more complete and subtle picture.

The Dunkirk Project 27th May 2010

For the 2010 commemorations, the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships reports on their website that over 50 little ships are expected to join the 70th anniversary commemorative return to Dunkirk, scheduled to sail on the 27th, and return on 29th/30th. The little ships have been gathering in Ramsgate over the last few days, in time for the ships’ blessings ceremonies on 26th (with echoes of the sea blessing ceremonies traditional in English coastal villages and sea ports at the end of May). Due to the turn in the weather, some ships have had an ‘exciting’ trip to Ramsgate, and some hadn’t yet arrived by the last report. Full details of this moving commemoration can be found at http://www.adls.org.uk/tl/content/70th-anniversary-commemorative-return-dunkirk/

(More news of the 2010 Return to Dunkirk from Wyldeboar:)

Several of the little ships overnighted unannounced in Quennborough (just adjacent to Sheerness) on Tuesday night 25th May. A good night was had by all in The Old House at Home, to such an extent that the entire lager cellar, including the extra laid in for the bank holiday weekend was drained to the last drop…

George Wilkinson May 27th 2010

We met Lt. Wilkinson yesterday having just arrived at Dunkirk from Dover, under orders with 30 MOs for the unenviable task of establishing dressing stations to assist the wounded during the evacuation. When we left him yesterday, ‘the first dressing station of the 171st Field Ambulance under active service conditions was then opened in an abandoned ambulance just to the left of a Sanitorium’. Here he continues his story:

May 27th 1940 The four M.O.s moved up to Bray Dunes and placed themselves under the command of I Corps. During this move Michael returning to look for one of the N.O.s became separated from the other three and later in the day became attached to the 126th Field Ambulance remaining in the A.D.S. at Bray Dunes with only their commanding officer, finally leaving Dunkirk via the Mole on Saturday evening and arriving back in Dover on Sunday. The other three moved about two miles inland where they established an A.D.S. under command of Lt. Babty in an estaminet on a cross roads. They remained there until the night of June 1st when having received orders to close the A.D.S. they drove by ambulance to the Mole from which they hoped to embark.

More from Lt. Wilkinson on 2nd June 1940 – Tatter’d colours. His story was sent to The Dunkirk Project by his son, George Wilkinson.

Roy Martin May 27th 2015

The Queen of the Channel was one of the excursion steamers that had been requisitioned to carry troops. On 27 May she was ordered to Dunkirk, berthing at the East Pier at 8pm. After she had loaded about fifty troops, the German gunners began shelling the pier and she was ordered to move. Captain O’Dell anchored his vessel about three-quarters of a mile off and launched four of her boats to ferry more soldiers from the beach. Two hundred were saved, but one of the boats, and its crew, was lost.

At 11pm she again went alongside the East Pier and loaded another 700 men, eventually setting sail at nearly 3am on 28 May.

(For what happened next, see Roy’s comment on tomorrow’s page: 28th May 1940 – Out there)

The Dunkirk Project 27th May 2015

The 2015 Return to Dunkirk was reported by the BBC in a very moving account of the commemoration ceremonies at Dunkirk:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-32856764

– and we’ve also heard from BG Bonallack’s family on board the Medway Queen in Ramsgate – but no details so far about the resulting state of the beer cellars in the home ports.

Liz Archer 27th May 2010

My father was on the beach at La Panne on the 27th May as his group couldn’t reach Dunkirk – he had been a clerk with GHQ in France for only a few weeks, then racing towards the coast evading the Germans all the way. It was while he was lying on the beach that he worked out it was the 27th and that meant it was his 22nd birthday. He returned to England with only the clothes he stood up in and said that the best meal he ever had was the bread and jam given him on the boat as it was days since they had had anything to eat.

Bernie Eastwood 2020

Is there a list of all who took part in the evacuation, i.e. merchant seamen, etc?

———-

The Dunkirk Project in reply

No, there isn’t a list of all who took part, as far as I know. There’s a list of all the ships, including merchant navy ships, that were known of at the time of publication, in David Divine’s ‘Dunkirk’, which has a 16-page Appendix B listing all the vessels from British ships to small craft that were ‘utilized’ in the operation, from The Ministry of War Transport lists, and then an Appendix C running to 37 pages, listing Dunkirk Honours and Awards from K.C.B. to Mentions in Dispatches – very moving reading, but not a comprehensive list of all who took part. I don’t know if we’ll ever know how many people were involved in the rescue, including all the medics, nurses and volunteers, as well as officially named staff. All commentators acknowledge that due to the ad hoc nature of Operation Dynamo, records were by no means scrupulous and comprehensive. But we have many individual records like ship’s logs and personal accounts, as well as the military and naval records, so there’s an enormous amount of information. The Dunkirk Project aims to contribute towards the mosaic of data by collecting hitherto unheard stories, and of course if anyone knows of fuller lists, I’d be glad to hear of them, too.

The Dunkirk Project 27th May 2020

The Medway Queen made her first of seven trips today 27th May in 1940, having provisioned to feed several hundred ‘somewhat peckish’ men. Read today’s story from the Medway Queen on the MQ Preservation Society‘s exciting daily blog pages – raising funds for the MQ’s continuing restoration and upkeep. They are aiming for £7000 – one for each of the 7000 people the Medway Queen rescued from Dunkirk:

https://www.medwayqueen.co.uk/news/dunkirk-day-by-day

jamesdragonfly March 9 2023

Hello, the Tough brothers rounded up over 100 ships for Dunkirk. Is there a list of them, or photos?

————–

The Dunkirk Project in reply

Hello James — yes, there’s a lot of fascinating information further to the story (at the beginning of this page) that you mention on the Tough Brothers and their boatyard, and the role they played in gathering and delivering requisitioned Thames craft for Dunkirk service. John Tough (grandson of the 1940s generation) is the archivist for the Association of Dunkirk Little ships and so the boatyard’s records are extensively researched and archived. I’m aiming to include a new page on them in the Heroic Ships series soon – so watch out for that feature.

The Dunkirk Project 28 May 2023

AD Divine, in his brilliant book Dunkirk gives some insights into the conditions the ships and little boats faced, not only when they reached Dunkirk, but on the way there and back:

‘It is difficult to conceive of the ordinary, routine troubles with which these ships had to deal. The first of these was the almost fantastically perilous navigation. The channels were quite inadequate for the amount of traffic they had to carry between some of the most dangerous shoals off the coast of Europe – in peace-time admirably marked, but now some of the light buoys had been sunk by the enemy, some by ships swinging wildly to avoid aircraft attack. Furthermore black smoke blew off the beaches, and there were new wrecks in the fairways, ships sunk by bombing or torpedo or collision.

All these the navigators had to contend with, and added to them was the constant stream of small craft moving at different speeds without lights. These little ships had to be avoided, and somehow for the most part they were. Without machine-gun fire, without shelling from the shore, without bombing, these things alone were enough to shake the nerve of the stoutest seaman.’

Please add your own comment or response in the comment box below

or email it to the.dunkirk.project@pottersyard.co.uk

Tomorrow, 28th May 1940 – Out there

Leave a comment