3rd June 1940 – Towards the end

Every day we received many more wounded at the ‘hotel’, the hospital at La Panne; we were kept extremely busy dressing wounds. Outside on the beaches were anti-aircraft guns, and every time they fired the whole building shook. At one time, a terrific barrage shattered the windows; fortunately the glass blew outwards. We had several air raids during the day, and the noise was terrifying.

Troops were continually lifted from the beaches, and at last the rumour spread that we also would be going home. It seemed too good to be true – but the day came when, having evacuated all our casualties, we received orders to move out. We were just packing our gear when Jerry dropped a stick of bombs across the beach, killing and wounding many men. A number were injured around the hotel when the remaining windows blew out, scattering glass. When the noise had died down, two of us set off down the beach in search of wounded.

Having evacuated our latest batch of casualties we finally moved off from the hospital, leaving behind an officer and eight men to look after the remaining wounded who were then moved to the Chateau. We marched off down the beach in single file, and behind us, shells screeched into La Panne; we saw one explode on the rear of the building we had just left.

(Corporal W McWilliam, RAMC, from Robert Jackson’s Dunkirk)

Meanwhile Major Philip Newman returned from his interview with General Alexander to request hospital ships, to the Chateau, the 12th Casualty Clearing Station, where all the remaining wounded were waiting evacuation. He, too, waited for orders.

The first was an invitation to send all the walking-wounded to the mole. Newman and his staff quickly went round the house and grounds, and collected a hundred men who were willing, and just about able, to shuffle along. They were packed into four lorries for transportation to the mole. After a dangerous journey, the men limped down the mole, and were helped on to a destroyer.

‘Then at about 9.45pm,’ wrote Newman, ‘just as the light was failing, we got a message at the Chateau to say a hospital ship was coming in. I called all the men together, and told them there was a slight chance, and that if we worked really hard all night, and got rid of all the wounded, we could get on the boat.’ Five ambulances full of wounded men were driven to the mole. Major Newman tells what happened next:

(Major Philip Newman’s story from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

We waited for an hour, but no hospital boat came. [Major Newman did not yet know that the two hospital ships sent for en clair had been bombed – one sunk, the other put out of action.]

At 11pm I saw the last of the BEF file past. We, with some marines, rushed a few of the stretchers half a mile up the jetty, and put them on a boat. At about 11.30pm the four commanders and brigadiers, and anybody else who was English, left in a pinnace, and there we were, left standing alone, forsaken by England, and only the Germans to look forward to. I can never forget that moment as long as I live. It gave me the greatest feeling of desolation I have ever had.

The rest of the stretchers we begged the French soldiers to take with them on to the boats, which they did with an ill grace. So we did at least do our duty, and got 25 more men to safety. One man on a stretcher, we actually chucked over, as the ship had already left the quay. He landed safely.

We arrived back at the Chateau. The boys had worked very hard to get the convoy ready, and then had given up hope, and simply gone to sleep on the ground in utter despair.

(Major Philip Newman, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. More news of Major Newman tomorrow, 4th June)

The last lifting was severely hampered by fog and smoke and besides the old known and charted wrecks in the approaches, there were now at least twelve new uncharted ones, and more wrecks in the harbour. HMS Express and HMS Shikari were the last ships to leave on 3rd June. The enemy tried to bomb Shikari; luckily the haze made their aim poor. These two ships carried between them about one thousand soldiers and the British pier parties. The only troops now remaining in Dunquerque were some non-combatants of the garrison and the few units still holding the fortress for the French.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder. More on the last to be rescued tomorrow, June 4th)

The first thing I’d pay tribute to is the men and the morale that we had in the battalion, which was absolutely wonderful. It was the most thrilling feeling to experience the spirit of the chaps who were with you. We had tremendous respect for the courage of our men and the way they held out when the Dunkirk withdrawal was going on. They never got to Dunkirk themselves. They were stopping the Germans interfering by land with the withdrawal of thousands and thousands of other people – which they did successfully. The battalion was practically wiped out doing it.

(Captain Francis Barclay, 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices. More news of the rearguard tomorrow, 4th June)

An improvised grave or way marker made from Thames driftwood

Ambulance driver Lillian Gutteridge was making her way to Dunkirk with an ambulance full of wounded patients. A German SS officer commandeered the ambulance and ordered her to abandon the stretcher-cases. She slapped his face, whereupon the SS officer stabbed her in the thigh, but the timely appearance of a troop of Black Watch soldiers saved her. Lillian Gutteridge then drove her ambulance to the railway, despite her wound, and managed to get her patients onto the Cherbourg train (which picked up another 600 wounded troops en route) and from Cherbourg eventually reached England.

(Story from Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Corps History by Julia Piggott on the QUARANC History website.

Is Harry [West, whom we last saw yesterday with his looted watches] the real animal behind the brave, laughing heroic boy panoply which the BBC spread before us nightly? – a natural human being, not made for shooting men, but for planting potatoes. I gather he’d shoot himself rather than go to France again. So it was at Waterloo, I suppose.

(Virginia Woolf’s diary. Harry West in fact rejoined his regiment and fought with it overseas until the end of the war.)

Suddenly Brigadier Beckwith-Smith drove up in his car. ‘Marvellous news, Jimmy,’ he shouted. ‘The best ever! It is splendid. We have been given the supreme honour of being the rearguard at Dunkirk. Tell your platoon, Jimmy, come on, tell them the good news.’

After all the months together, I knew 15 Platoon very well, and had not the slightest doubt that they would accept this information with their usual tolerance and good humour. However I did not think they would class it as ‘marvellous’ and ‘the best ever’.

‘I think it had better come from you sir.’

‘Right,’ he replied, and after telling them to remain seated, made known to them the change of plan.

(2nd Lt Jimmy Langley of the 2nd Coldstream Guards, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. Jimmy Langley was wounded and taken to the Chateau, where his arm was amputated by surgeon Major Philip Newman. He survived to become a P.o.W. and was repatriated to England in 1941, where he became one of the leading lights of MI9, helping prisoners of war escape and travel home.)

I hoped and believed that last night would see us through, but the French, who were covering the retirement of the British rearguard, had to repel a strong German attack, and so were unable to send their troops to the pier in time to be embarked. We cannot leave our allies in the lurch, and I must call on all officers and men detailed for further evacuation tonight, and let the world see that we never let down an ally.

(Vice Admiral Ramsay’s directions, issued at 10am on 3rd June, from Hugh Segbag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

There were in fact still many men to be rescued; it is probable that there were at least 30,000 men still in the area, and it was essential that a tremendous effort should be made to lift the last of them. Ammunition was by now quite exhausted, and any question of holding even a bridge-head in the town itself was hopeless.

Princess Maud and Royal Sovereign were the last of the passenger ships to leave Dunkirk. HMS Shakari, Sun IV, Sun XV and Tanga went in to the Mole at the same time on Monday 3rd June. This was almost the very last of the loading – the last desperate effort. Already, in addition to the bombing and the shelling, machine-gun fire from the Germans in the streets of the town was beginning.

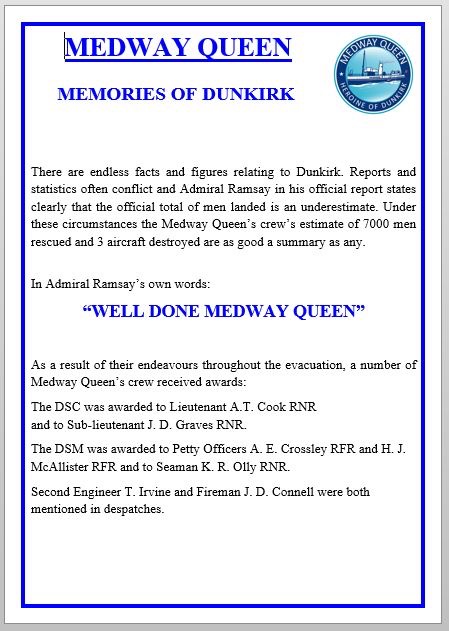

HMM Medway Queen made her last passage. She had established the mine-sweepers’ record of seven trips, a magnificent performance. She went alongside the Mole again, and very shortly after she had made fast a shell-burst threw a destroyer against her stern lines, cutting them. Both ships swung out and Medway Queen lost her brow. Men who were at the moment coming down it managed to fling themselves aboard as it fell. Almost immediately afterwards she was in trouble again, being rammed by a cross-channel steamer. She picked up 367 French troops among others on this trip, considerably incapacitated by various troubles.

At 3.30 HMS Shakari was still lying alongside the quay. Only the wreckage of Dunkirk and its flames lay between the advancing Germans and the Mole. The men that were left were weaponless and defenceless. At 3.40am, with the German machine-guns stuttering in the nearer streets, having taken every man she could get on board, the destroyer pulled out. To Shakari, one of the oldest of the destroyers in service in the Royal Navy (she was built in 1919) fell the honour of being the last ship to leave Dunkirk.

(from AD Divine’s Dunkirk)

Ages passed. We began to give up hope of a boat. Suddenly out of the blackness, rather ghostly, swam a white shape which materialised into a ship’s lifeboat, towed by a motor-boat. It moved towards us and came to a stop twenty yards in front of the head of the queue we all hailed, dreading they hadn’t seen us. But they risked a few more yards. So fearful was I that the boat might move off and leave us that I struggled to the head of the queue and waded forward crying: ‘Come on the 2004th!’

Higher rose the water every step we took. Soon it reached my arm-pits, and was lapping the chins of the shorter men. The blind urge to safety drove us on whether we could swim or not. Our feet just maintained contact with the bottom by the time we reached the side of the boat.

Four sailors in tin-hats began hoisting the soldiers out of the water. It was no simple task. Half the men were so weary and exhausted that they lacked strength to climb into the boat unaided. The gunwale stood three feet above the surface of the water. Reaching up I could just grasp it with the tips of my fingers. When I tried to haul myself up I couldn’t move an inch. A great dread of being left behind seized me.

Two powerful hands reached over the gunwale and fastened themselves into my arm-pits. Another pair of hands stretched down and hooked-on to the belt at the back of my great-coat. Before I had time to realise it I was pulled up and pitched head-first into the bottom of the boat.

The boat was now getting crowded. The moment came when the lifeboat could not hold another soul. And we got under weigh, leaving the rest of the queue behind to await the next boat. There and then on that dark and sinister sea, an indescribable sense of luxurious contentment enveloped me. The grey flank of H.M.M. Medway Queen, paddle steamer, loomed in front of us, her shadowy decks already packed with troops from the beaches. In a minute or two our boatload was submerged in the crowd. Irresistible drowsiness seized us…

It was a beautiful sunny June morning. Not a speck of cloud in the blue sky. And there in the pearly light that a slight haze created we saw the finest sight in the world.

“Ramsgate!” I exclaimed.

“England,” murmured the A.C.P.O.

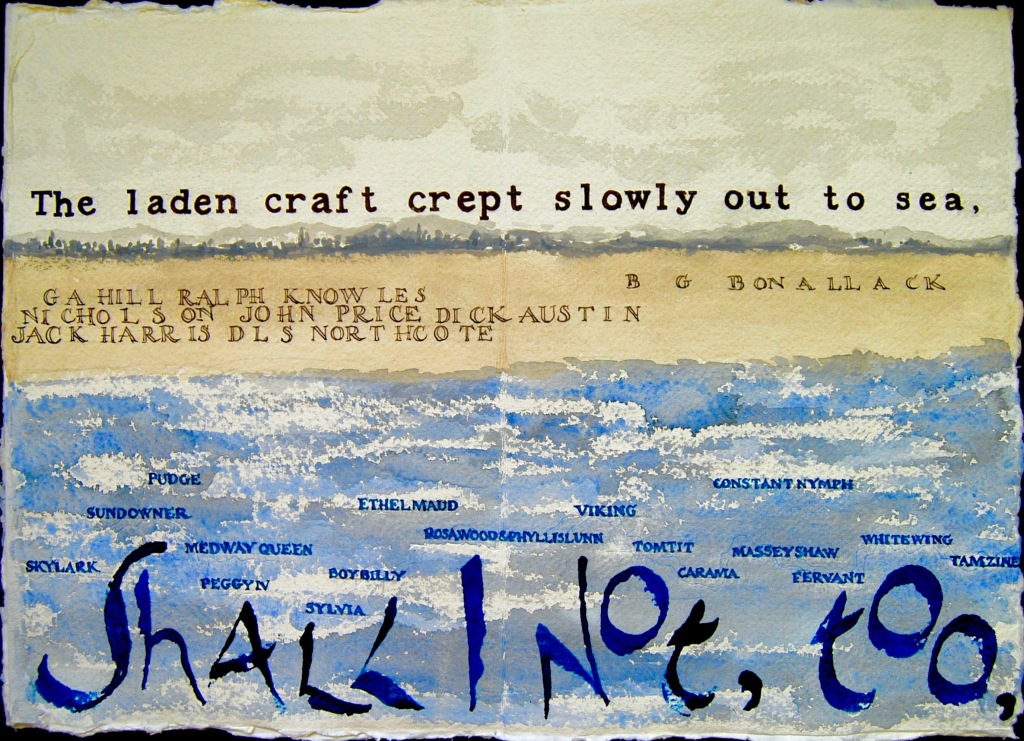

(from Return via Dunkirk by Gun Buster, ending his best-selling account of the heroic rearguard action of Y Battery, 2004th Field Regiment R.A., ‘the last battery in the B.E.F. to come out of action’. Gun Buster and his colleagues were brought back on HMM Medway Queen, the first in our series of Heroic ships. Gun Buster is the pen-name of Dick Austin – Capt. R.A. Austin of 368 Battery, 92nd Field Regiment Royal Artillery, whose colleague in arms ‘Boyd’ is Capt. B.G. Bonallack, soldier-poet whose story runs through Thames to Dunkirk. More on BG Bonallack here.)

The last ships carrying BEF soldiers left Dunkirk shortly before 11pm. The total number of soldiers evacuated was 288,000 (including some 193,000 BEF troops), a miraculous figure compared with the 45,000 the Admiralty had originally mentioned to Vice-Admiral Ramsay. General Alexander and Captain Tennant who had overseen the evacuation then toured the beaches and the harbour in a motor boat, calling for any British soldiers to show themselves. None did, and at 11.30pm Tennant sent the following signal to Dover, which at the beginning of Operation Dynamo he had never imagined would be appropriate: ‘BEF evacuated.‘

(Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Dunkirk)

Lucky Weather

Mere English, this Armada thing again

(the genius for last-minute muddle through,

the lucky weather)

Sunday sailors

who messed about in boats

now take their baptism of fire.

Heroes – how not – courage beyond, of course.

An island race, etc.

The sea shall have them.

For those in peril – the sea, the sea

never dealt death like this.

Compassless little ships to ferry home

every man England expects will do

not question why.

(Frances Bingham)

Comments

The Dunkirk Project 3rd June 2010

For many, it wasn’t over yet. Tomorrow in 4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk we hear more stories from the very last troops to be lifted from Dunkirk, the people left behind, the troops still in France who hadn’t made it to Dunkirk in time for evacuation with Operation Dynamo, and more from the rearguard; as well as about troops sent back into France immediately after Operation Dynamo, the merchant ships, tugs and steamers that rescued thousands of people in the subsequent evacuation operations – and some retrospective views reaching some surprising conclusions about Dunkirk 1940.

One of the most evocative broadcasts ever made about Dunkirk was recorded by JB Priestley on 5th June 1940, in which he pays homage to the little ships. He speaks of Dunkirk as ‘another English epic’, and his voice breaks as he talks about a ship he knows well, his own local ferry, the Isle of Wight channel steamer ‘our Gracie Fields‘, who will not return from her last ‘excursion to Hell’.

‘Never again will we board her at Cowes. She has paddled and churned away for ever. This little steamer is immortal, she’ll go sailing proudly down the years in the epic of Dunkirk.’

– and his last thought is of how ‘our great-grandchildren’ will remember the ‘little pleasure steamers’ of Dunkirk, ‘so absurd, and yet so grand and gallant’.

JB Priestley can be heard on the BBC Dunkirk archive at http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/dunkirk/14310.shtml

Words in Company 3rd June 2010

The end of the evacuation of Dunkirk seems to mark the moment when people first realised that invasion of Britain was possible – even imminent. One of the most poignant evocations of that time is Humphrey Jennings film-poem of 1940, ‘Listen to Britain’, where (in luminous black and white) people eat their sandwiches in the London sunshine outside the National Gallery or listen to Myra Hess playing the piano inside. The patchwork of layered images – people at work in factories or dancing to ‘Roll out the barrel’, the moonlit sea and waving corn – makes an extraordinarily subtle and moving picture of the country, which seems immensely precious and fragile, and to be a human construction, made up of the individuals who inhabit it.

The Dunkirk Project 3rd June 2010

While our view of Dunkirk owes so much to contemporary published accounts (ie from 1940) from writers like David Divine, John Masefield, Vera Brittain, JB Priestley et al, another major resource for The Dunkirk Project has been the work of later historians in gathering stories from unpublished archives (Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices, and Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk to name a few – please see Sources page).

Uncovering stories that reflect different aspects of the event (including how it continues to affect our lives) must help us to learn from our collective story, even if it doesn’t lead directly to explicit and simple conclusions. The questions raised when we acknowledge the continued relevance of our collective experience are bound to be complex; that seems a good reason for attempting to address them by re-evaluating the myth, rather than accepting and repeating it. Only by doing that can we honour our past.

The Dunkirk Project 3rd June 2015

Roy Martin, who has sent in some great stories of the merchant navy’s involvement in Dunkirk and the following evacuation operations, finished the story of the elderly tramp steamer Dorrien Rose with her return to Newhaven for a rest, and the honours awarded to her entire crew. Tomorrow, 4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk, he highlights another story of endurance, this time on the part of the rescued – Polish troops on board SS Alderpool on a long hungry journey.

The Dunkirk Project 3rd June 2015

AD Divine’s splendid book Dunkirk has an overwhelming list of honours and awards which runs to some 39 pages. Among these hundreds of DSOs, DSMs and Mentions in Despatches are:

DSM for Skipper GD Olivier (Laurence Olivier’s brother ‘Dickie’, a Royal Naval reservist on board the yacht Marsayru)

Mention in Dispatches for Ali Khan and Abdul Mohammed, firemen on board the Dorrien Rose (as well as honours for the entire crew of the elderly tramp steamer whose story concluded yesterday)

DSC for Captain George Johnson, Master of the Royal Daffodil (whose unflagging journeys we have followed throughout the nine days);

and a DSM for the Royal Daffodil‘s Donkeyman, Albert Delamain

DSM for the Massey Shaw‘s Sub-Officer Aubrey John May of the London Fire Brigade, and Mentions in Despatches for three other firemen and crew members

a Mention in Despatches for Mrs. A Goodrich (who we met as a stewardess on board the hospital ship Dinard

Mention in Despatches for fireman John Develand Connell, among 7 honours for crew members of the Medway Queen

DSM for Mr Basil Arthur Smith on the Constant Nymph

and quietly among this long list, a modest mention for a DSM for Mr AD Divine on Little Ann.

Among all these perhaps the most moving to me are the awards for cooks, canteen assistants, stewards (and a stewardess), surgeons, signalmen, sickberth attendants, stokers, ship’s boys, and retired servicemen, as well as lifeboat and minesweeper crews, the posthumous awards and those twice honoured: ordinary people being extraordinarily courageous in the most dangerous circumstances.

Linda Rowley 3rd June 2015

My mother’s first husband didn’t make it out of Dunkirk. He was taken prisoner there by the Germans and died in a POW camp in Poland of nephritis.

My mother’s cousin, however, did make it out on one of the last ships. He told me the story of sleeping in a barn (he said his unit was in disarray) and of making it to the shore to be picked up.

He had a photo of himself and 2 other soldiers on board, wrapped in blankets. He said they fed him a huge breakfast and how good it tasted. And another photo of himself and other soldiers just returned, in a newspaper clipping; the byline was a Tracy Harrison, probably on the 50th anniversary, but I was never able to locate the news article or that photo again. Before he passed away (on the anniversary of D-Day nearly 10 years ago) he had moved into a care home and threw all his mementos in the trash.

Thank you for this project; it is marvellous to read all these stories.

—————–

The Dunkirk Project in response to Linda Rowley 3rd June 2015

The newspaper cutting shown above on this page is the one Linda Rowley mentions. Luckily it was not thrown out but preserved by Alec Harrison, recently found by Linda and sent to The Dunkirk Project, along with a photo of Alec the last time she saw him in Worthing in his 80’s. She also sent some more of Alec’s story:

‘Alec was so blase about doing his bit, yet he was sort of our family Forrest Gump: in addition to being at Dunkirk, he was in North Africa, I believe, wherever Monty was, because he looked enough like him to be used and dressed as Montgomery at one point in his army travels. I think he was an ambulance driver at some point, definitely in the Army Medical Corps. Also, he was aboard a ship near Gibraltar that was bombed and a few of the blokes down in the engine room were killed, I believe – I only wish I had paid more attention to his very interesting stories, or that he had written them down! – I know he said the ship limped into port. Upon his return home, he worked for a local pharmacy, but then took the test to become a London taxi driver. He knew SO much about London history and landmarks. He was a very interesting man. He lived in Camden for years, drove a London cab for decades, then retired to Worthing. He died a few years ago on June 6th, the anniversary of D Day.

‘My uncle Syd was in Egypt, and my dad was in London and at the end of the war in Holland and Germany. My grandfather was a gunner in WWI, my brother was in Vietnam, my husband was in the army, one son in USAF, one a Marine, and my daughter a brief stint in the U.S. Navy. My other uncle was in France and got a combat medal and was wounded. I’m very proud of my family’s contribution and glad they all survived to tell the tale – and I’m glad I’ve never been bombed nor had to pick up a weapon.’

Many thanks to Linda for sharing this treasured memento and Alec Harrison’s story.

Graham Alcock October 26th 2017

My father was a Lance Sergeant in the Second Battalion the Coldstream Guards in 1939. His name was John Alcock and he served with his brother Charles in the same battalion.

I know a little about his experiences. In one instance he said he had had to shoot an old woman who had been terribly wounded in an air attack by fighters. She had been in a group of civilians who had been fleeing the German advance.

His brother Charles remembers meeting my father once on the retreat. My father came out of some woods leading a file of men and there was Charles with a food station handing out grub to the men as they went by.

When my father and his battalion went to the mole to board their ship he was asked to go back to the start of the mole for some wounded. As a result he missed this boat – Sabre – but managed to get another. He was reported missing to his parents. He slept the first night home in a Dover warehouse and heard men screaming in their sleep. When he re-joined his battalion it was at Walton near Wakefield and my mother cycled thirty miles to see him there from Goole. By 1943 he was in 2 SAS.

—————

The Dunkirk Project in response to Graham Alcock October 26th 2017

Thanks so much Graham for sending this story about some of your father’s experiences at Dunkirk. Your mother probably would have cycled all the way to Dunkirk if she could. And how strange for him to meet his brother Charles like that – even if they were in the same regiment. It’s extraordinary how many people encountered their siblings, brothers, sons or fathers there in that maelstrom. You would think the chances of meeting accidentally among 300,000 people were very slight, but it does highlight how each person in that great crowd was an individual, part of a family – and The Dunkirk Project was initially inspired by this very idea, and aims to commemorate each individual involved, including all the people waiting desperately for news in Goole.

——————

Graham Alcock replies

Mother saw father through the camp fence wire for a time at Walton.

Wendy Maher December 28th 2018

Does anyone have anything on Frank Starr who had been sleeping as he was utterly exhausted and woke to see the very last little boat leave. As a strong swimmer he swam out to this boat and luckily got hauled aboard! He was my uncle and his children would dearly love to know anything.

Dennis O Sullivan June 3rd 2019

My Dad came back on the Princess Maud, his name was Jim Sullivan (I believe 51st Highland Regiment). I would love to know where the Princess Maud docked back in England on the 4th June 1940; it carried 1270 soldiers back from Dunkirk.

My dad later went on to fight in North Africa, Sicily and Normandy on D-Day where he was injured and taken back to Southampton to Netley Royal Hospital; I have no enlistment no for him so getting information is not easy. He was a tank driver with 7th armour in North Africa. If anybody can find out any scrap of information I would be very grateful.

Dennis O Sullivan

—————

The Dunkirk Project in response to Dennis O Sullivan 3rd June 2019

Thanks so much, Dennis, for sending in these details about your father, Jim Sullivan. It’s extraordinary to think of soldiers being evacuated from Dunkirk and then later going on to fight in North Africa, Sicily and Normandy. Yes, it’s difficult to find more information without his enlistment number, but we do have more information about the Princess Maud.

There were in fact unusually two Princess Mauds in service at Dunkirk, one a Southend pleasure boat, one a personnel ship – and this second one is the one your father was on. The first was lost early in the evacuation, but her story is worth telling as it throws some light on the scene. She was one of four Southend pleasure boats (the others were Shamrock, Canvey Queen and Queen of England) which set off together for Dunkirk with ‘utmost speed’. These boats had probably never ventured further than the estuary before, taking passengers on pleasure trips, and they were to experience something very different from their daily rounds. Canvey Queen dropped out of the convoy when she developed engine trouble off Shoeburyness, and the Queen of England was badly damaged in a collision with HM Skoot Tilly in the turmoiled waters round Dunkirk when the remaining pleasure boats eventually neared their destination. Allan Barrell, the Captain of Shamrock described the scene approaching Dunkirk waters:

‘Ahead everything was blazing, oil and petrol tanks were continually exploding near the coast, the noise and flames were beyond description. I was feeling a bit weary about the feet, cramp through cold was aggravating me, it was about sixteen hours since we left Canvey.’

CP Dick from the motor-boat Advance gives a vivid picture of how the small ships operated when they reached Dunkirk, and the frustrating job awaiting them:

‘Told to get as many men as possible from the beach to the waiting ships. Proceeded to do so. Took Advance as close in as seemed safe in slight surf caused by other ships’ wash and bombs. The troops at this time were rather disorganised, not only units, but nationalities being mixed. Eventually proceeded alongside destroyer and troops embarked therein. Returned to beach for more. Shortly after we left this destroyer appeared to be hit by one or more bombs. Troops in rather better order now, so got second boatload off without much trouble. On third trip managed to get Advance close enough in for men to wade or swim out.’

At this point a bomb fell close to Advance‘s starboard side, and though there were no casualties, the whaler she was working with was sunk, so they took the men out of her and abandoned her. Captain Dick continues his story:

‘When things had quietened a little, returned and got our men into a transport.

After this we picked up anything we could find near the beach, whalers, pontoons, rafts, shore boats and even bathing floats and canoes, taking the men from them to the nearest ship of any sort that we could find.’

Advance continued to rescue many men in this way, sustaining serious damage herself, and eventually made for Ramsgate, where she had to be beached to save her from sinking alongside Ramsgate quay.

The second Princess Maud was a passenger ship that came out of Margate with Royal Daffodil and Royal Sovereign. She was badly shelled on the way to Dunkirk on May 30th 1940, but made swift repairs and was in service again by the end of the evacuation, arriving at Dunkirk on Monday 3rd June with Royal Sovereign just before midnight. Her captain Henry Clarke gives a graphic account of the difficulties facing the rescue boats on this last night of the operation:

‘We arrived off Dunkirk breakwater at 11.57pm. The narrow fairway was crammed to capacity, with all varying types of ships bound in and out. Wrecks dotted the harbour here and there. The only light was that of shells bursting, and the occasional glare of the fires. I shouted to the nearest steamer alongside “How long will you be?”

They answered “A quarter of an hour.”

This fifteen minutes must have been a nightmare for the engineers with having to constantly keep clear of traffic, wrecks, etc. Shells were coming from the east and west by this time, and aircraft were overhead.

‘Just before half-past twelve an outward bound transport struck us on the starboard bow, inflicting slight damage.

‘At 12.45 a French trawler struck us on the port quarter and almost capsized herself; no damage to us.

‘At 12.55 we proceeded alongside the vacated berth at the extreme end of the eastern jetty. Troops then clambered aboard all ways, no gangways available. Dogs of all kinds got aboard somehow. There was no confusion whilst a steady line of men was directed along the jetty by several members of the crew.

‘At 1.40 am the flow of troops thinned out, only stragglers came along. I was told that the port was going to be blocked at 2.30am.

‘At 1.50 we were fairly well packed, so I cast off after being told that was the last of the troops, although one other steamer was ahead loaded. A shell fell in the berth we had just vacated.’

These details of the night of your dad’s embarkation on Princess Maud are from AD Divine’s extraordinary witness account Dunkirk (Faber, 1945), and he concludes:

The personnel ships had ended their superb story of heroism and sacrifice at 1.40am, when Princess Maud cast off for the last time from Dunkirk Mole.

Captain Henry Clarke, Master of Princess Maud, was Mentioned in Dispatches. After Princess Maud to leave Dunkirk was HMM Medway Queen, among whose cargo of rescued soldiers was BG Bonallack, whose witness account forms one of the lines of Thames to Dunkirk which inspired The Dunkirk Project.

But the motor-boat Advance‘s experience shows that the ships and boats didn’t necessarily return to the port they had sailed from or were requisitioned from, so although the Princess Maud set off from Margate she may have returned to one of its fellow towns – Ramsgate or Dover. AD Divine gives credit where it’s due:

‘Somehow an organisation arose that dealt with the men as they landed, fed them, gave them some means of communicating with their homes, patched the wounded, took care of the dying, and transported the fit men into the hinterland. In its way, the enthusiasm that made that possible was as remarkable as most things in the nine days. At Ramsgate the ARP organisations and women’s services combined to provide the canteens that met each party of men as it stumbled off the long arm of the eastern wall.

They carried huge trays of cake and rolls and sandwiches, enormous cans of tea. Children carried stacks of postcards and pencils, and collected them as the men scribbled a brief message upon each. To keep all this going all Ramsgate and Margate and the villages round about threw in their effort. Bread was a primary necessity. For days it was almost impossible to buy a loaf in the shops and local bakers. Flour was commandeered and hundreds of housewives settled down, away from recognition, to work solidly at their ovens for days on end turning the flour into cake and biscuits.

And what happened in Ramsgate and its fellow towns, what its ARP and its women’s services, its clubs and its leagues did there, was done at Sheerness and Margate, at Dover and Folkestone and Newhaven.

These things have small glory, but they were an integral part of Dunkirk – a necessary, a vital part.’

I haven’t yet been able to find out exactly where Princess Maud docked on 4th June, but I will make efforts to find out. If any of our readers or contributors can provide further information, that will be most welcome.

Liz Mathews for The Dunkirk Project

Richard Jay May 23 2020

My father, Harold Jay, was called up on his 21st birthday October 1939. He served in the RASC and went with the BEF to France. Sadly I have forgotten much of what he said about his experiences, and he was always rather reticent. He did tell me about walking along the beach to get to the mole, and that he was taken off on the Harvester on one of its last trips, probably 31 May or 1 June. I have a photograph of him not long after he returned, looking very handsome, but with eyes wide open as if he had been through an appalling experience – as indeed he and everyone there had. I just wanted to put this down as we start the 80th commemoration of this astonishing event.

—————

Liz Mathews in response to Richard Jay May 23 2020

What a way to mark a 21st birthday! I believe it’s very important for us to remember the devastation of Dunkirk, that people like your father carried with them for the rest of their lives. So often reticent, as you say – almost all our contributors note that it was never an easy subject to be talked about, but the scars are there. Piecing together the wider picture, true detail by detail is a way of collectively remembering these real experiences and their lifelong consequences, and I believe this is the most important part of any commemoration.

Richard Halton https://www.medwayqueen.co.uk

Liz, I’m involved with Medway Queen‘s restoration and always keen to learn more of her time at Dunkirk and to share what we know.

Please add your own comment or response in the comment box below

or email it to the.dunkirk.project[at]pottersyard.co.uk

Tomorrow, 4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk

Leave a comment