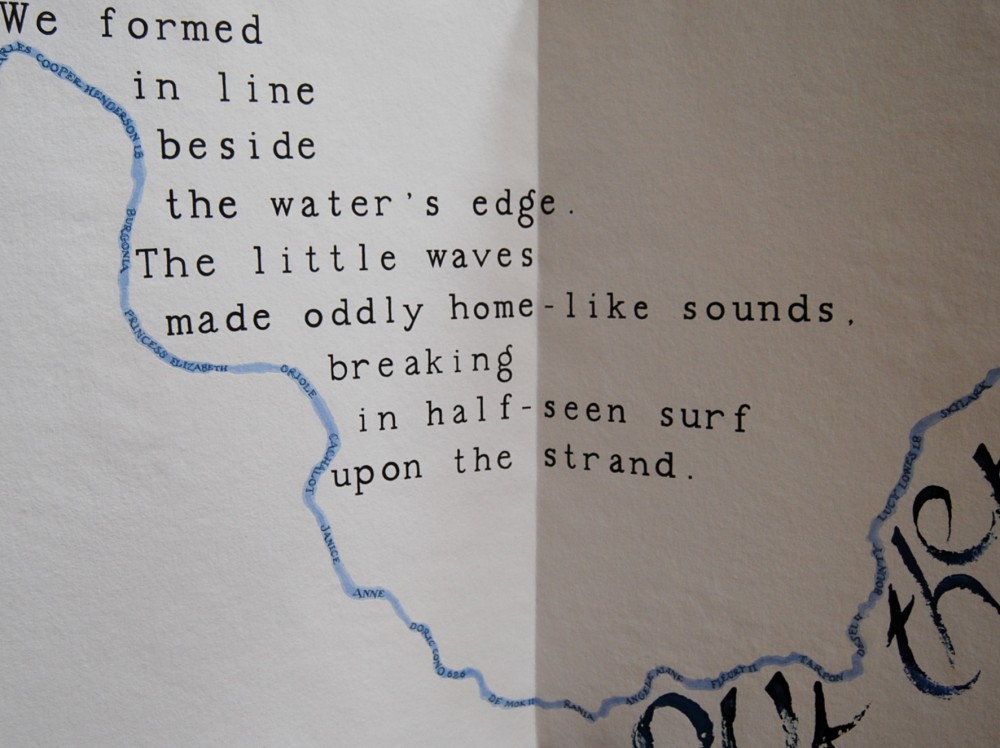

The picture will always remain sharp etched in my memory – the lines of men wearily and sleepily staggering across the beach from the dunes to the shallows, falling into little boats, great columns of men thrust out into the water among bomb and shell splashes. The foremost ranks were shoulder deep, moving forward under the command of young subalterns, themselves with their heads just above the little waves that rode in to the sand. As the front ranks were dragged aboard the boats, the rear ranks moved up, from ankle deep to knee deep, from knee deep to waist deep, until they, too, came to shoulder depth and their turn.

(David Divine, Miracle at Dunkirk)

The docks at Dunquerque could now only be used by small vessels, as ships had been bombed and sunk within the Main Basin. Ships could still go alongside the wall in the tidal Basin, but the approaches to it were made almost impassable by the intense heat and the continuous bombing. There remained only the wooden East Pier, which might well give way under the strain of several thousand tons butting against it. Since embarkation from the pier alone would not suffice to lift the numbers in time, it was planned that the men should get into boats upon the beaches and be ferried to ships anchored in the channel off the shore. All ships coming near the coast were bombed. The losses in men were very great; in ships severe, and in boats enormous. No ship returned from the beach undamaged. Nothing but heroic industry and utter self-sacrifice kept the ships steadily plying to and fro.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder)

The beach was one vast sea of bodies. I had never seen so much dejection. Soldiers felt that they had been left there. Some seemed to have given up, but personally I didn’t. There was one place I was going, and that was back to England. There was panicking, but most of us managed to keep our heads. One chap scrounged a tin of bully beef and laid it out like a picnic, tucked his napkin in, then apologised that he couldn’t supply the wine because the butler happened to be away that day.

(Corporal Henry Palmer, 1/7th Batallion, Queen’s Royal Regiment, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Sub-Lt Alfred Weaver had no sooner left Ramsgate than the Quijijana‘s engine caught fire; dousing it with the extinguisher, Weaver ploughed on, but the minute he sighted Dunkirk the old yellow-funnelled pleasure launch began shipping water. Finding the bilge pump inoperative, Weaver and his crew had to bale desperately with their service caps. For the first time, Weaver saw the brass plate affixed to the bulwarks – ‘Licensed to ply between Chertsey and Teddington’ – and understood. That stretch of the river Thames, he knew, measured only fourteen miles.

(Richard Collier, from The War at Sea, ed. John Winton)

There they stood, lined up like a bus queue, right from the dunes, down the shore, to the water’s edge, and sometimes up to their waists beyond. They were as patient and orderly, too, as people in an ordinary bus queue. There were bombers overhead and artillary fire all around them. They were hungry and thirsty and dead-beat; yet they kept in line, and no-one tried to steal a march on anyone else. Most of them even managed to summon up an occasional joke or wisecrack.

(Ian Hay, ‘one of the volunteers’, from The Battle of Flanders)

‘The situation of the British and French Armies, now engaged in a most severe battle and beset on three sides from the air, is evidently extremely grave. The surrender of the Belgian Army in this manner adds appreciably to their grievous peril. But the troops are in good heart and are fighting with the utmost discipline and tenacity…

I expect to make a statement to the House on the general position when the result of the intense struggle now going on can be known and measured. This will not, perhaps be until the beginning of next week. Meanwhile, the House should prepare itself for hard and heavy tidings.’

(Winston Churchill, House of Commons, 28th May 1940, quoted in AD Divine’s Dunkirk. Churchill’s promised statement to the House on 4th June 1940 is quoted on that day’s page – Beyond Dunkirk.)

The Massey Shaw, the London fireboat moored at Blackfriars Bridge was among the first to arrive at Bray Dunes, east of Dunkirk – she made three trips altogether. Nineteen lifeboats went to Dunkirk, particularly useful because of their shallow draft, that allowed them to get close to the beaches, and their steadiness. The brand-new Guide of Dunkirk lifeboat, funded by the Girl Guides Association went straight from the boat builders; the Rosa Woodd & Phyllis Lunn, the Shoreham lifeboat paid for by a private legacy made three trips to Dunkirk; the Lord Southborough lifeboat went from Margate with a civilian crew, and RNLI lifeboats from all round the south and east coast and the estuary went, including Louise Stephens from Great Yarmouth and Aldeborough No 21 from the Isle of Wight. Lady Haig, a 27′ clinker elm and oak boat used as a privately owned lifeboat on the Goodwin Sands, the Thomas Kirk Wright an inland lifeboat from Poole Harbour, the Countess Wakefield and the Cecil and Lilian Philpott from Newhaven all brought many men home.

(Ships’ stories from several sources including the website of the Association of Little Ships of Dunkirk. More little ships’ stories throughout the nine days, and more from the Massey Shaw tomorrow 29th May)

On the second night we went in, there was order. There was an officer at the head and he called out, ‘Coxswain, how many do you want?’ And I would tell him, and he would count them off. Any wounded they would pass over their heads, and you’d take the wounded off first.

(Coxswain Thomas King, HMS Sharpshooter, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Sapper Alexander Graham King, ‘the mad hatter’ played his accordion in his top hat to entertain the waiting troops on the beaches for seven days before he joined a queue himself. We do like to be beside the seaside, presumably.

(From the Imperial War Museum archive)

Words came tumbling from Rhayader now. He must go to Dunkirk. A hundred miles across the Channel. A British army was trapped there on the sands, awaiting destruction at the hands of the advancing Germans. The port was in flames, the position hopeless. He had heard it in the village when he had gone for supplies. Men were putting out from Chelmbury in answer to the government’s call, every tug and fishing boat or power launch that could propel itself was heading across the Channel to haul the men off the beaches to the transports and destroyers that could not reach the shallows, to rescue as many as possible from the Germans’ fire.

He said: ‘Men are huddled on the beaches like hunted birds, Frith, like the wounded and hunted birds we used to find and bring to sanctuary… They need help, my dear, as our wild creatures have needed help, and that is why I must go. It is something that I can do.’

‘I’ll come with ‘ee, Philip.’

Rhyader shook his head. ‘Your place in the boat would cause a soldier to be left behind, and another, and another. I must go alone.’

(from The Snow Goose by Paul Gallico)

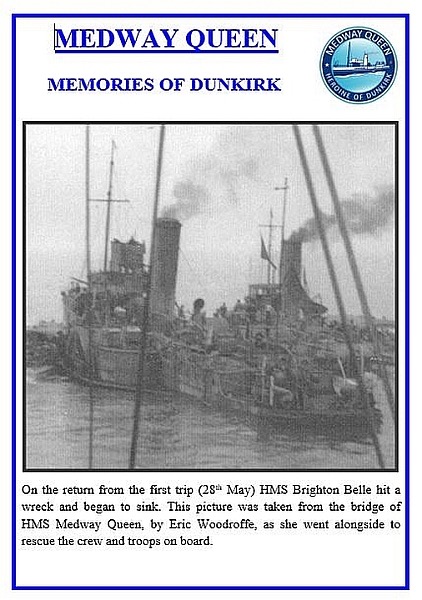

Pudge, a 1922 barge of the London and Rochester Trading Company went to Dunkirk by sail-power alone, its captain Bill Watson an old chap with gold earrings. Sir Malcolm Campbell’s Bluebird and Bluebird II both went, and Cabby, a wooden sailing barge that usually plied between the London docks and Whitstable. The New Britannic, a 1930 passenger boat from Ramsgate brought back 3000 men altogether; the Medway Queen, a 1924 paddle-steamer was one of the first to arrive at Dunkirk, bringing back 7000 men over seven runs. She picked up John Hayworth of Rochester in mid-channel, surrounded by bodies from his wrecked ship, and she was one of the last ships involved in Operation Dynamo, bringing back some of the troops from the rear-guard, including BG Bonallack.

(Ships’ stories from several sources including the website of the Association of Little Ships of Dunkirk. More little ships’ stories throughout the nine days, and more on the Medway Queen on 3rd June – Towards the end. ‘Memories of Dunkirk’, stories from the Medway Queen’s website are featured throughout the nine days news pages in the by-now familiar blue boxes.)

A megaphone asked if there was anyone who would volunteer to crew up a fishing boat, where some of the crew had been machine-gunned. This boy of 17 – who’d been sunk twice that day – volunteered immediately. He got cheered by the sailors and the soldiers who were on board. When we got alongside at Dunkirk and secured, a file of Scottish soldiers who were wearing khaki aprons over their kilts, came along led by an officer who’d got his arm in a sling. He called out to the bridge, ‘What part of France are you taking us to?’ One of our officers called back, ‘We’re taking you back to Dover.’ So he said, ‘Well, we’re not bloody well coming.’ They turned round and went back to continue their war with the Germans on their own. It was something remarkable.

(Ordinary Seaman Stanley Allen, aboard HMS Windsor, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Not all the volunteers had signed T124 – the form that made them Royal Naval Volunteers for a month – for they prized their independence too much. Some in any case were there despite official qualms: Stewardess Amy Goodrich, the only woman to be awarded a Dunkirk decoration, swore that so long as the nurses sailed in the hospital ship Dinard, she’d sail too.

(Richard Collier, from The War at Sea, ed. John Winton)

The following day, we left again, proceeded to Dunquerque and this time went alongside the pier to take off troops. We returned to Margate without incident [!] and landed the men on the beach.

(Captain G Johnson of the Royal Daffodil – more of his wonderfully laconic account tomorrow and every day until 2nd June)

Under bombs and guns, men are carried across the Channel, not only by troop-ships, but by private yachts, river tugs, harbour life-boats and coastal pleasure steamers – the ‘Saucy Sallies’ of the summer season. The rescuers are not wholly male. ‘Blast my sex!’ cries a girl who offers her private yacht, to be told that men alone are eligible. The powers-that-be turn a blind eye in her direction, and suspect that she finds her way to Dunkirk.

(Vera Brittain, from England’s Hour)

It was now that we saw for the first time the bombing of the beaches. The first wave of early evening bombers roared over us towards Dunkirk, two miles away. We watched them circle and dive. Then sounded the thud, thud of the explosions.

We weren’t altogether unaware of what was happening on the beaches. Our progress along the road had been at a snail’s pace, and we’d picked up a very good idea of the horrors going on from scraps of conversation with the infantry.

“Have you heard that they’re gunning ’em as well as bombing ’em?”

“Some have been on the beach three days before they got a boat.”

“Got safely on a destroyer and it was bombed. Most of ’em blown to bits…”

“I’ve just been told that they gun the fellows as they are swimming to the lifeboats.”

“What will it be like when we get there?”

“Shall we get there?”

“What d’you think our chance is?”

(from Return via Dunkirk by Gun Buster, whose story continues tomorrow 29th May)

from Ode Written during the Battle of Dunkirk, May 1940

The old guns

barked into my ear. Day and night

they shook the earth in which I cowered

or rained round me

detonations of steel and fire.

One of the dazed and disinherited

I crawled out of that mess

with two medals and a gift of blood-money.

No visible wounds to lick – only a resolve

to tell the truth without rhetoric

the truth about war and about men

involved in the indignities of war.

In the silence of the twilight

I hear in the distance

the new guns.

I listen, no longer apt in war

unable to distinguish between bombs and shells.

As the evening deepens

searchlights begin to waver in the sky

the air-planes throb invisibly above me

There is still a glow in the west

and Venus shines brightly over the wooded hill.

Unreal war! No single friend

links me with its immediacy.

It is a voice out of a cabinet

a printed sheet, and these faint reverberations

selected in the silence

by my attentive ear.

Presently I shall sleep

and sink into a deeper oblivion.

(Herbert Read, from The Hundred Years’ War, ed. Neil Astley, Bloodaxe 2014)

To add a comment to today’s page, please click on the date in the menu top left, and you’ll find the comments at the end of the page.

Tomorrow, 29th May 1940 – Nightmare