On 4th June Dunkirk fell to the Germans.

(from Five Days in London, John Lukacs)

The signal ‘Operation Dynamo now completed’ circulated by the Admiralty on 4th June by no means implied that all BEF troops had been evacuated from France. There were still more than 100,000 British soldiers south of the River Somme; the British 51st Highland Division had to secure nineteen miles of the front line. ‘On this day alone 23 officers and over 500 other ranks were missing, wounded or killed. June 5th must have been the blackest day in the history of the battalion.’

(from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

It’s a complete mess. There are guns everywhere, as well as countless vehicles, corpses, wounded men and dead horses. The heat makes the whole place stink. Dunkirk itself has been completely destroyed. There are lots of fires burning. Amongst the prisoners are Frenchmen, and blacks, some of them not wearing uniforms, real villains, scum of the earth. We move to Coxy de Bains by the beach. But we cannot swim because the water is full of oil from the sunk ships, and is also full of corpses. At midnight there is a thanksgiving ceremony on the beach, which we watch, while looking at the waves in the sea, and the flames in the distance, which show that Dunkirk is still burning.

(German staff officer who entered Dunkirk on 4th June 1940, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

The ‘miracle’ of the Dunkirk evacuation was well known to those who were alive in 1940. The accepted version is that all 338,226 members of the British Expeditionary Force were saved from the beaches near Dunkirk by the Royal Navy and an armada of ‘little ships’ who volunteered for the task. Churchill described the rescue of ‘every last man’ of the BEF as a ‘miracle of deliverance’. There is no doubt that these two groups performed magnificently, but, as with so many ‘miracles’, the story includes some myths. One was that only Royal Naval vessels and the ‘little ships’ were involved; the other that all of the BEF were evacuated.

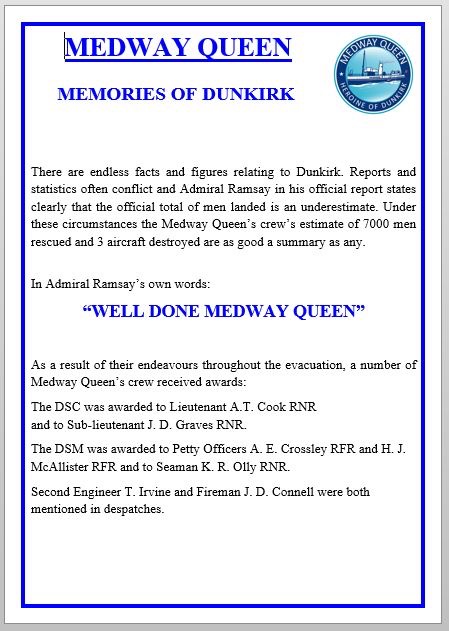

In fact almost as many troops were left in France, most to be evacuated in the following three weeks by merchant ships. Certainly the Navy rescued the majority from Dunkirk and it fell to the various Admirals to organise all of the evacuations, but merchant ships carried more than 90,000 troops to safety. About three quarters of these were saved by railway steamers, ferries and excursions ships (generally described as ‘Packets’). The rest were carried by cargo vessels, coasters, tugs and barges. A further 5,548 stretcher cases were moved by other railway steamers acting as hospital carriers. In addition the Navy operated Dutch schuyts and British paddle steamers; these last still manned by their peacetime crews and civilian volunteers.

(Roy V. Martin, from Ebb and Flow: Evacuations and Landings by Merchantmen in World War Two)

The little boats all summoned again, as if to fetch off more troops. 20,000 of our men cut off.

(Virginia Woolf’s diary for 12th and 13th June 1940)

Some French soldiers were lifted from Dunkirk harbour during the next midnight, by French and English ships, the last ship (the Princess Maud) leaving at 1.50am on the 4th. As she left, a shell fell in the berth she had occupied a moment before. Though the lifting was finished, some useful cruising was done later, to pick up stragglers. The RAF and a number of motor-boats cruised over the Channel, and helped to find and save men wrecked in a transport and a barge. On the evening of June 12th, some survivors were seen by a British aeroplane, who reported them to the patrols; a motor-boat went out at once and brought them off. These must have been among the last to be saved. The numbers lifted and brought to England from Dunkirk alone during the operation were: British 186,587; French 123,095 and those brought by hospital ships etc 6,981, making a total of 316,663.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder)

On the beaches and in the dunes north of Dunkirk, thousands of light and heavy weapons lay on the sands, along with munitions crates, field kitchens, scatttered cans of rations and innumerable wrecks of British army trucks.

‘Damn!’ I exclaimed to Erwin. ‘The entire British Army went under here!’

Erwin shook his head vigorously. ‘On the contrary! A miracle took place here! If the German tanks and Stukas and navy had managed to surround the British here, shooting most of them, and taking the rest prisoner, then England wouldn’t have any trained soldiers left. Instead the British seem to have rescued them all – and a lot of Frenchmen too. Adolf can say goodbye to his Blitzkreig against England.’

(Bernt Engelman, Luftwaffe pilot, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Philip Newman, the surgeon who we left yesterday at the Chateau, was captured by the Germans along with the wounded at the Chateau. In January 1942 he escaped for the second time (he had been recaptured after his first escape) and made it back to England. Later he became one of Britain’s leading orthopaedic surgeons and in 1962 he operated on Churchill, who had broken his hip. He was finally honoured in 1976, when he was appointed CBE.

(from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

‘When a week ago I asked the House to fix this afternoon for a statement, I feared it would be my hard lot to announce from this box the greatest military disaster in our long history.

I thought, and some good judges agreed with me, that perhaps from 20,000 to 30,000 men might be re-embarked, but it certainly seemed that the whole of the French First Army and the whole of the British Expeditionary Force north of Amiens and the Abbeville gap would be broken up in the field or else have to capitulate for lack of food and ammunition.

This was the hard and heavy tidings for which I called on the House and the nation to prepare themselves a week ago.’

(Winston Churchill, House of Commons 4th June 1940, quoted by AD Divine in his Dunkirk – who adds with restrained pride the following conclusion:)

Not 20,000 men but 337,131 came safe to the ports of England.

The first attempt to rescue those left behind was named Operation Cycle: this was hampered by fog, the lack of ships’ wirelesses and heavy shelling. The evacuation ‘fell far short of Admiral James’s early hopes’. About 8,000 men of the 51st Highland Division were cut off and ordered to surrender; but by 13 June over 15,000 other troops had been saved.

Reinforcements were sent through St Malo; two thirds didn’t get beyond the port before they were recalled; wits in Southampton said that BEF meant ‘back every Friday’

Operation Aerial began on 15 June when 133 ships were sent to Breton ports; most of the 140,000 British troops were saved then. These vessels also mounted an evacuation of the Channel Islands. On 17 June the British liner Lancastria was sunk off St Nazaire.

(Roy Martin, from After Dynamo, May 2015 for The Dunkirk Project; his story continues later on this page.)

Roughly four o’clock in the afternoon the sirens went again. There was an instant attack, a terrific bang and blast which blew me off my feet – straight into the lap of an army officer. Another bomb went off and the ship lurched and started heeling over. Another bomb went off. Machinery like trucks, guns, stuff that was on the deck – human beings all hurtled down into the rails of the ship, into the water. One of my most vivid pictures is of the big masts running parallel to the water, and people running along this and jumping off. I saw a rope and grabbed it. I couldn’t swim so I had to get hold of something that would keep me afloat. I grabbed an oar between my legs and a kitbag under each arm and just floated there.

(Sergeant Peter Vinicombe, Wireless operator, 98 Squadron RAF, aboard Lancastria, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

At least 2,710 people drowned, making this Britain’s worst maritime disaster.

(Roy Martin, After Dynamo, continuing below)

We were practically the last to embark on the Lancastria. By this time, she had round about 6,000 troops and air force on board. We were assigned to palliasses right on the bottom of the hold. It was pretty grim and, having a strong sense of self-preservation, I thought, ‘Well, on the trip home, if we get attacked by submarines or hit a mine, we wouldn’t have a chance down there – particularly if the lights have all gone.’ So I decided to stay on the top deck. When she was hit I went to the bow to have a look back, and she was sinking slowly in the water. So I said to this chap, ‘Well, I’m a swimmer. I’m over the side.’ I just looked down about a thirty foot drop, took my tin helmet off, my uniform, my boots, clutched my paybook and my French francs and jumped over the side. When I broke surface I swam about a hundred yards and came across a plank, which looked as if it had been blown off one of the hatches. So I sat on that, and the thing that surprised me was how calm I felt. I thought, ‘Well, I’ll sit on this. You’ll never see anything like this again.’ Fifty yards away from me, men were singing ‘Roll out the barrel’.

(Corporal Donald Draycott, Fitter, 98 Squadron, aboard the Lancastria, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

The sinking of the Lancastria was the subject of a BBC documentary and a page on the BBC History site tells the story in full with some moving images. Click here for a link to the archived page.

It’s something that you look back on with astonishment – that from the little trawler which picked us up, we were able to watch the final lurching and sinking of the Lancastria. She overturned completely in the end, so you could see the propellors, and even then you could see men standing on her upturned bows, afraid to jump into the sea. That was a pretty awful sight to behold. That was awful.

(Private William Tilley, Clerk, Royal Army Service Corps, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

After the rescues from Breton ports and the evacuation of the Channel Islands, the ships moved to Bordeaux, where much treasure was also saved. They then went on to St Jean de Luz, near the Spanish border. Embarkations only ceased when the Armistice came into force on 25 June. More of those rescued from these ports were Polish and Czech troops and civilians. The Polish liners Batory and Sobeiski embarked their countrymen and British cargo ships saved many more. Further British and Allied troops and civilians were lifted from southern France. Voyages from western France took days, rather than hours, those from the south took weeks to reach the UK.

During the three operations the Royal Navy sent 102 ships and 45 requisitioned Dutch coasters. The Merchant Navies, mainly the British, provided 129 passenger ships and 141 cargo ships – an awesome response.

(Roy Martin, from After Dynamo. More from Roy Martin in today’s comments, including an account from Miss R Andrews who was rescued by the Ettrick, one of the last passenger ships to leave St Jean de Luz.)

Just then (it was almost midnight), we had our first taste of the kindness of a great people; ladies of the British Red Cross (I had no idea who warned them, or who had even thought of warning them) went from one compartment to the other with hot tea and pieces of delicious freshly made cake. What a luxury after the stale bread we had eaten for the last five days. We even received some warm milk for the children. My wife and the nurse could not restrain their tears. I also saw tears in the eyes of the Red Cross volunteer, a very kind and distinguished-looking lady with white hair, who was helping us. We were far from the Germans. That cup of tea and piece of cake had comforted us morally as well as physically.

(Paul Timbal, among those evacuated from Bordeaux on the Broompark on 19th June 1940, part of Operation Aerial. Timbal’s story is told in The Suffolk Golding Mission by Roy V. Martin)

Photo from archive of Polish Institute & Sikorski Museum in London, contributed by Roy Martin

It is said that many thousands – it is even said that four-fifths of them – have got back. A few days ago one thought they must either surrender or die. They have fought their way out in the greatest, strangest rearguard action ever known. Corunna, when one thinks how much fiercer and crueller war is today, cannot compare with it. However, it is a victory over adversity, not over Germans; it is a moral, not a physical victory.

(Sarah Gertrude Millin, 1 June 1940, from World Blackout.)

General Bernard Law Montgomery criticised the shoulder ribbons issued to the troops, marked ‘Dunkirk’. They were not ‘heroes’. If it was not understood that the army suffered a defeat at Dunkirk, then our island home was now in grave danger. Churchill saw things in much the same way: ‘Wars are not won by evacuations.’

(from Five Days in London by John Lukacs)

In retrospect, it was Dunkirk that lost Germany the war, because it suddenly brought Britain to her senses – made us realise that, with all our allies surrendered to the enemy, we alone had to carry the fight. The rest is history.

(Arthur Addis, Ammunition Officer, HQ, Third Division, BEF, quoted from the BBC website archive of the Dunkirk Evacuation by kind permission of his wife.)

No British soldiers were left on the beach and it is remembered as a success rather than a retreat – ‘snatching glory out of defeat’.

(The entry for ‘Dunkirk’ in the Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1991)

I, like so many others had taken for granted the history of England, of which Nelson was a part. And I knew that I, too, should in future feel a sense of responsibility.

(Second Officer Nancy Spain, WRNS, from Voices from the War at Sea, ed. John Winton)

FROM HIS MAJESTY THE KING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND MINISTER OF DEFENCE, 4th JUNE 1940, Buckingham Palace.

I wish to express my admiration of the outstanding skill and bravery shown by the three Services and the Merchant Navy in the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Northern France. So difficult an operation was only made possible by brilliant leadership and an indomitable spirit among all ranks of the Force. The measure of its success – greater than we had dared to hope – was due to the unfailing support of the Royal Air Force and, in the final stages, the tireless efforts of naval units of every kind.

While we acclaim this great feat, in which our French Allies too have played so noble a part, we think with heartfelt sympathy of the loss and sufferings of those brave men whose self-sacrifice has turned disaster into triumph.

GEORGE R.I. (Letter quoted in AD Divine’s Dunkirk, Appendix A; Appendix B contains the official list of the hundreds of ships, boats and other craft which took part in Operation Dynamo, and Appendix C lists 36 pages of Dunkirk Honours and Awards)

A brutal, desperate adventure forced on us by the most dire disaster.

(AD Divine, from Dunkirk. Divine went to Dunkirk on board the White Wing with Rear Admiral Taylor and was awarded the DSM)

This morning I lingered over my breakfast, reading and re-reading the accounts of the Dunkirk evacuation. I felt as if deep inside me there was a harp that vibrated and sang, like the feeling of seeing suddenly a big bed of clear, thin red poppies in all their brave splendour. I forgot I was a middle-aged woman who often got up tired and also had backache; somehow I felt everything to be worthwhile, and I felt glad I was of the same race as the rescuers and rescued.

(5th June 1940 diary entry in Nella Last’s War: A Mother’s Diary, quoted in John Lukacs’ Five Days in London)

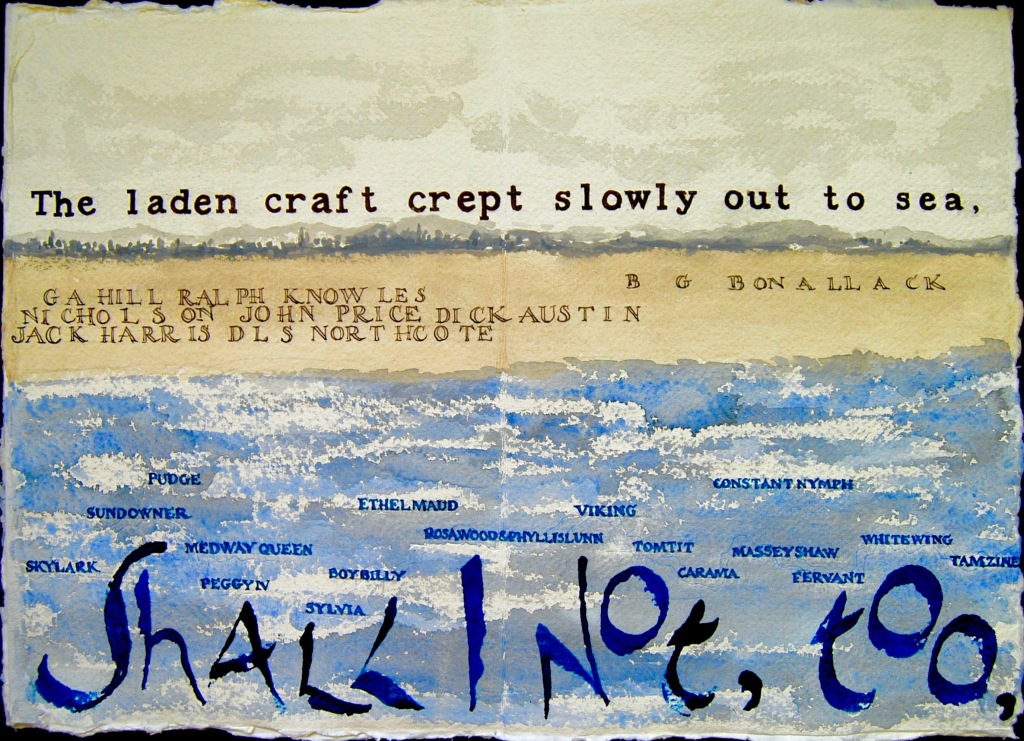

The little ships, the unforgotten Homeric catalogue

of Mary Jane and Peggy IV, of Folkestone Belle,

Billy Boy, and Ethel Maud, of Lady Haig and Skylark,

the little ships of England brought the Army home.

(Philip Guedalla, 1941)

On Sunday morning news came over the radio – Britain had declared war on Germany. What I feared more than my own death, war raged by everyone against everyone else, had been unleashed for the second time. Once again I walked down to the city of Bath for a last look at peace. It lay quiet in the noonday sunlight and seemed just the same as ever. People went their usual way, walking with their usual gait. They were in no haste, they did not gather together in excited talk, and for a moment I wondered: ‘Don’t they know what has happened yet?’ But they were English, they were used to concealing their feelings. They didn’t need drums and banners, noise and music, to fortify them in their tough and unemotional resolution.

I knew what war meant, and as I looked at the crowded, shining shops I saw a sudden vision of the shops I had seen in 1918, cleared of their goods, cleaned out, I saw, as if in a waking dream, the long lines of careworn women waiting outside food shops, the grieving mothers, the wounded and crippled men, all the mighty horrors of the past come back to haunt me like a ghost in the radiant midday light. I remembered our old soldiers, weary and ragged, coming away from the battlefield; my heart, beating fast, felt all of that past war in the war that was beginning today. And I knew that yet again all the past was over, all achievements were as nothing – our own native Europe, for which we had lived, was destroyed and the destruction would last long after our own lives. Something else was beginning, a new time, and who knew how many hells and purgatories we still had to go through to reach it?

The sunlight was full and strong. As I walked home, I suddenly saw my own shadow going ahead of me, just as I had seen the shadow of the last war behind this one. That shadow had never left me all this time, it lay over my mind day and night. Perhaps its dark outline lies over the pages of this book. But in the last resort, every shadow is also the child of light, and only those who have known the light and the dark, have seen war and peace, rise and fall, have truly lived their lives.

(The closing paragraphs of The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig, first published in German in 1942, translated by Anthea Bell and published by Pushkin Press in 2009.)

To read or add to today’s comments and conversations, please go to 4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk in the menu top left, and you’ll find the comments at the foot of the page.