Every day we received many more wounded at the ‘hotel’, the hospital at La Panne; we were kept extremely busy dressing wounds. Outside on the beaches were anti-aircraft guns, and every time they fired the whole building shook. At one time, a terrific barrage shattered the windows; fortunately the glass blew outwards. We had several air raids during the day, and the noise was terrifying.

Troops were continually lifted from the beaches, and at last the rumour spread that we also would be going home. It seemed too good to be true – but the day came when, having evacuated all our casualties, we received orders to move out. We were just packing our gear when Jerry dropped a stick of bombs across the beach, killing and wounding many men. A number were injured around the hotel when the remaining windows blew out, scattering glass. When the noise had died down, two of us set off down the beach in search of wounded.

Having evacuated our latest batch of casualties we finally moved off from the hospital, leaving behind an officer and eight men to look after the remaining wounded who were then moved to the Chateau. We marched off down the beach in single file, and behind us, shells screeched into La Panne; we saw one explode on the rear of the building we had just left.

(Corporal W McWilliam, RAMC, from Robert Jackson’s Dunkirk)

Meanwhile Major Philip Newman returned from his interview with General Alexander to request hospital ships, to the Chateau, the 12th Casualty Clearing Station, where all the remaining wounded were waiting evacuation. He, too, waited for orders.

The first was an invitation to send all the walking-wounded to the mole. Newman and his staff quickly went round the house and grounds, and collected a hundred men who were willing, and just about able, to shuffle along. They were packed into four lorries for transportation to the mole. After a dangerous journey, the men limped down the mole, and were helped on to a destroyer.

‘Then at about 9.45pm,’ wrote Newman, ‘just as the light was failing, we got a message at the Chateau to say a hospital ship was coming in. I called all the men together, and told them there was a slight chance, and that if we worked really hard all night, and got rid of all the wounded, we could get on the boat.’ Five ambulances full of wounded men were driven to the mole. Major Newman tells what happened next:

(Major Philip Newman’s story from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

We waited for an hour, but no hospital boat came. [Major Newman did not yet know that the two hospital ships sent for en clair had been bombed – one sunk, the other put out of action.]

At 11pm I saw the last of the BEF file past. We, with some marines, rushed a few of the stretchers half a mile up the jetty, and put them on a boat. At about 11.30pm the four commanders and brigadiers, and anybody else who was English, left in a pinnace, and there we were, left standing alone, forsaken by England, and only the Germans to look forward to. I can never forget that moment as long as I live. It gave me the greatest feeling of desolation I have ever had.

The rest of the stretchers we begged the French soldiers to take with them on to the boats, which they did with an ill grace. So we did at least do our duty, and got 25 more men to safety. One man on a stretcher, we actually chucked over, as the ship had already left the quay. He landed safely.

We arrived back at the Chateau. The boys had worked very hard to get the convoy ready, and then had given up hope, and simply gone to sleep on the ground in utter despair.

(Major Philip Newman, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. More news of Major Newman tomorrow, 4th June)

The last lifting was severely hampered by fog and smoke and besides the old known and charted wrecks in the approaches, there were now at least twelve new uncharted ones, and more wrecks in the harbour. HMS Express and HMS Shikari were the last ships to leave on 3rd June. The enemy tried to bomb Shikari; luckily the haze made their aim poor. These two ships carried between them about one thousand soldiers and the British pier parties. The only troops now remaining in Dunquerque were some non-combatants of the garrison and the few units still holding the fortress for the French.

(John Masefield, Nine Days Wonder. More on the last to be rescued tomorrow, June 4th)

The first thing I’d pay tribute to is the men and the morale that we had in the battalion, which was absolutely wonderful. It was the most thrilling feeling to experience the spirit of the chaps who were with you. We had tremendous respect for the courage of our men and the way they held out when the Dunkirk withdrawal was going on. They never got to Dunkirk themselves. They were stopping the Germans interfering by land with the withdrawal of thousands and thousands of other people – which they did successfully. The battalion was practically wiped out doing it.

(Captain Francis Barclay, 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices. More news of the rearguard tomorrow, 4th June)

An improvised grave or way marker made from Thames driftwood

Ambulance driver Lillian Gutteridge was making her way to Dunkirk with an ambulance full of wounded patients. A German SS officer commandeered the ambulance and ordered her to abandon the stretcher-cases. She slapped his face, whereupon the SS officer stabbed her in the thigh, but the timely appearance of a troop of Black Watch soldiers saved her. Lillian Gutteridge then drove her ambulance to the railway, despite her wound, and managed to get her patients onto the Cherbourg train (which picked up another 600 wounded troops en route) and from Cherbourg eventually reached England.

(Story from Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Corps History by Julia Piggott on the QARANC History website.

Is Harry [West, whom we last saw yesterday with his looted watches] the real animal behind the brave, laughing heroic boy panoply which the BBC spread before us nightly? – a natural human being, not made for shooting men, but for planting potatoes. I gather he’d shoot himself rather than go to France again. So it was at Waterloo, I suppose.

(Virginia Woolf’s diary. Harry West in fact rejoined his regiment and fought with it overseas until the end of the war.)

Suddenly Brigadier Beckwith-Smith drove up in his car. ‘Marvellous news, Jimmy,’ he shouted. ‘The best ever! It is splendid. We have been given the supreme honour of being the rearguard at Dunkirk. Tell your platoon, Jimmy, come on, tell them the good news.’

After all the months together, I knew 15 Platoon very well, and had not the slightest doubt that they would accept this information with their usual tolerance and good humour. However I did not think they would class it as ‘marvellous’ and ‘the best ever’.

‘I think it had better come from you sir.’

‘Right,’ he replied, and after telling them to remain seated, made known to them the change of plan.

(2nd Lt Jimmy Langley of the 2nd Coldstream Guards, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. Jimmy Langley was wounded and taken to the Chateau, where his arm was amputated by surgeon Major Philip Newman. He survived to become a P.o.W. and was repatriated to England in 1941, where he became one of the leading lights of MI9, helping prisoners of war escape and travel home.)

I hoped and believed that last night would see us through, but the French, who were covering the retirement of the British rearguard, had to repel a strong German attack, and so were unable to send their troops to the pier in time to be embarked. We cannot leave our allies in the lurch, and I must call on all officers and men detailed for further evacuation tonight, and let the world see that we never let down an ally.

(Vice Admiral Ramsay’s directions, issued at 10am on 3rd June, from Hugh Segbag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

There were in fact still many men to be rescued; it is probable that there were at least 30,000 men still in the area, and it was essential that a tremendous effort should be made to lift the last of them. Ammunition was by now quite exhausted, and any question of holding even a bridge-head in the town itself was hopeless.

Princess Maud and Royal Sovereign were the last of the passenger ships to leave Dunkirk. HMS Shakari, Sun IV, Sun XV and Tanga went in to the Mole at the same time on Monday 3rd June. This was almost the very last of the loading – the last desperate effort. Already, in addition to the bombing and the shelling, machine-gun fire from the Germans in the streets of the town was beginning.

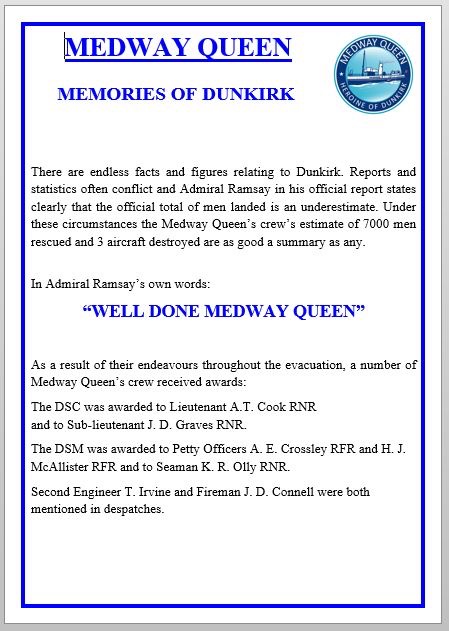

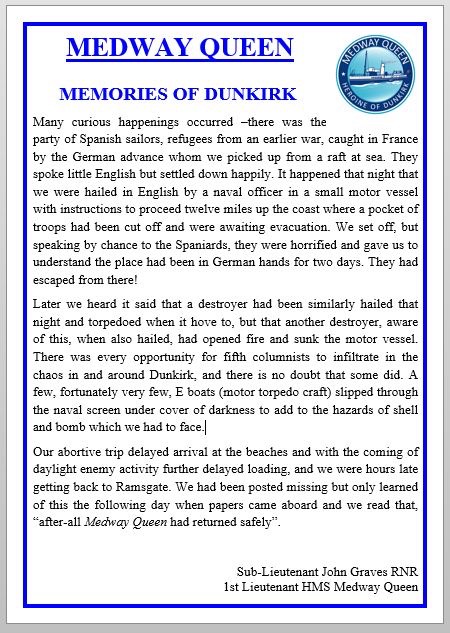

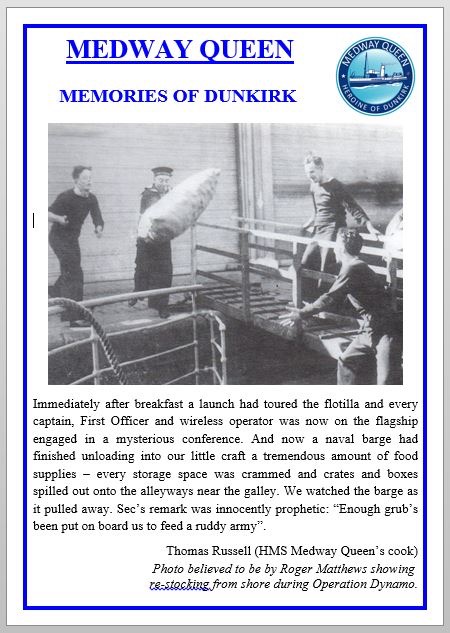

HMM Medway Queen made her last passage. She had established the mine-sweepers’ record of seven trips, a magnificent performance. She went alongside the Mole again, and very shortly after she had made fast a shell-burst threw a destroyer against her stern lines, cutting them. Both ships swung out and Medway Queen lost her brow. Men who were at the moment coming down it managed to fling themselves aboard as it fell. Almost immediately afterwards she was in trouble again, being rammed by a cross-channel steamer. She picked up 367 French troops among others on this trip, considerably incapacitated by various troubles.

At 3.30 HMS Shakari was still lying alongside the quay. Only the wreckage of Dunkirk and its flames lay between the advancing Germans and the Mole. The men that were left were weaponless and defenceless. At 3.40am, with the German machine-guns stuttering in the nearer streets, having taken every man she could get on board, the destroyer pulled out. To Shakari, one of the oldest of the destroyers in service in the Royal Navy (she was built in 1919) fell the honour of being the last ship to leave Dunkirk.

(from AD Divine’s Dunkirk)

Ages passed. We began to give up hope of a boat. Suddenly out of the blackness, rather ghostly, swam a white shape which materialised into a ship’s lifeboat, towed by a motor-boat. It moved towards us and came to a stop twenty yards in front of the head of the queue we all hailed, dreading they hadn’t seen us. But they risked a few more yards. So fearful was I that the boat might move off and leave us that I struggled to the head of the queue and waded forward crying: ‘Come on the 2004th!’

Higher rose the water every step we took. Soon it reached my arm-pits, and was lapping the chins of the shorter men. The blind urge to safety drove us on whether we could swim or not. Our feet just maintained contact with the bottom by the time we reached the side of the boat.

Four sailors in tin-hats began hoisting the soldiers out of the water. It was no simple task. Half the men were so weary and exhausted that they lacked strength to climb into the boat unaided. The gunwale stood three feet above the surface of the water. Reaching up I could just grasp it with the tips of my fingers. When I tried to haul myself up I couldn’t move an inch. A great dread of being left behind seized me.

Two powerful hands reached over the gunwale and fastened themselves into my arm-pits. Another pair of hands stretched down and hooked-on to the belt at the back of my great-coat. Before I had time to realise it I was pulled up and pitched head-first into the bottom of the boat.

The boat was now getting crowded. The moment came when the lifeboat could not hold another soul. And we got under weigh, leaving the rest of the queue behind to await the next boat. There and then on that dark and sinister sea, an indescribable sense of luxurious contentment enveloped me. The grey flank of H.M.M. Medway Queen, paddle steamer, loomed in front of us, her shadowy decks already packed with troops from the beaches. In a minute or two our boatload was submerged in the crowd. Irresistible drowsiness seized us…

It was a beautiful sunny June morning. Not a speck of cloud in the blue sky. And there in the pearly light that a slight haze created we saw the finest sight in the world.

“Ramsgate!” I exclaimed.

“England,” murmured the A.C.P.O.

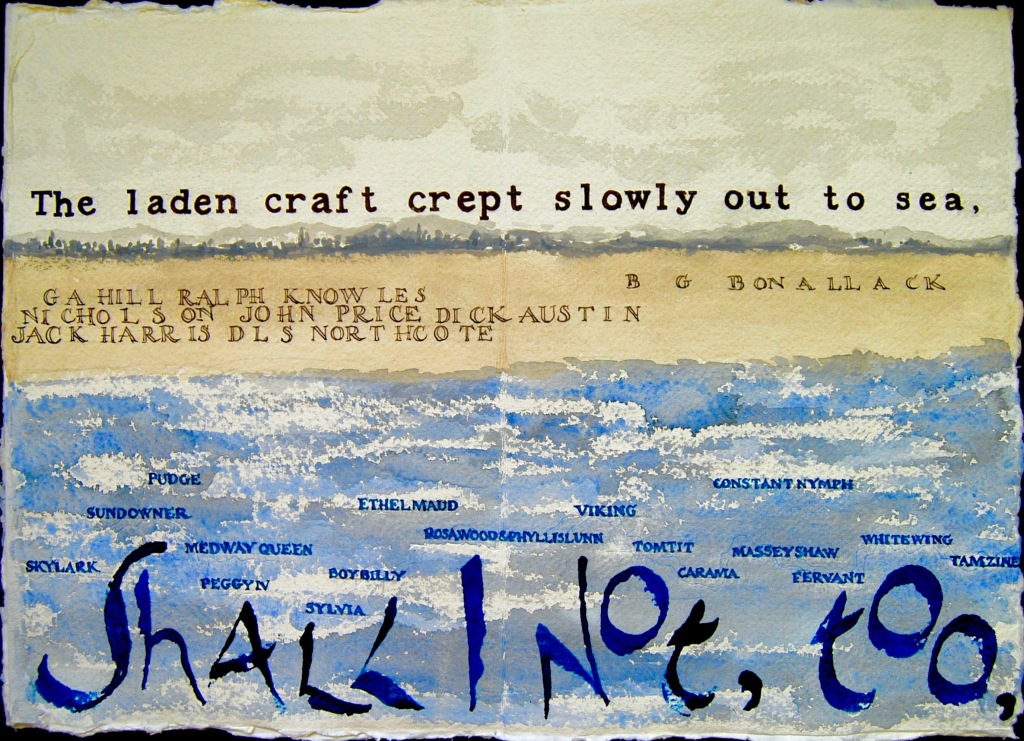

(from Return via Dunkirk by Gun Buster, ending his best-selling account of the heroic rearguard action of Y Battery, 2004th Field Regiment R.A., ‘the last battery in the B.E.F. to come out of action’. Gun Buster and his colleagues were brought back on HMM Medway Queen, the first in our series of Heroic ships. Gun Buster is the pen-name of Dick Austin – Capt. R.A. Austin of 368 Battery, 92nd Field Regiment Royal Artillery, whose colleague in arms ‘Boyd’ is Capt. B.G. Bonallack, soldier-poet whose story runs through Thames to Dunkirk. More on BG Bonallack here.)

The last ships carrying BEF soldiers left Dunkirk shortly before 11pm. The total number of soldiers evacuated was 288,000 (including some 193,000 BEF troops), a miraculous figure compared with the 45,000 the Admiralty had originally mentioned to Vice-Admiral Ramsay. General Alexander and Captain Tennant who had overseen the evacuation then toured the beaches and the harbour in a motor boat, calling for any British soldiers to show themselves. None did, and at 11.30pm Tennant sent the following signal to Dover, which at the beginning of Operation Dynamo he had never imagined would be appropriate: ‘BEF evacuated.‘

(Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Dunkirk)

Lucky Weather

Mere English, this Armada thing again

(the genius for last-minute muddle through,

the lucky weather)

Sunday sailors

who messed about in boats

now take their baptism of fire.

Heroes – how not – courage beyond, of course.

An island race, etc.

The sea shall have them.

For those in peril – the sea, the sea

never dealt death like this.

Compassless little ships to ferry home

every man England expects will do

not question why.

(Frances Bingham)

To read or add to the comments and conversations for this day, please go to 3rd June 1940 – Towards the end in the menu top left, and you’ll find the comments at the foot of the page.

Tomorrow, 4th June 1940 – Beyond Dunkirk

–

–