Safe & well in England. Just in case the wire doesn’t connect.

We were told to embark as many people from the jetties as we could. Most of them were stretcher-cases and walking wounded. They looked like a beaten army – they weren’t really, but they looked it. We cleared the mess decks to make room for the stretchers. The walking cases were pushed into corners. There were two or three hundred of them on board, plus about sixty of us crew. We tried to feed them but we ran out of food. They seemed shocked and were very, very quiet. I don’t think they realised what was happening to them. A lot of them had never seen warfare. We got the chaps off at Portsmouth. Those that could walk marched off the jetty, heads up and shoulders back.

(Ordinary seaman Dick Coppeard, Royal Navy, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Things now became much worse. From midnight until five in the morning, the shelling increased to such a pitch that of the two hospital ships sent in for wounded, only one was able to go in to bring them off. The other lay off the harbour entrance for four hours, but could not get in. Four troopships tried to get in and failed. One entered at dawn, loaded up, and was returning, when she was heavily bombed. At five o’clock the enemy let loose a monstrous air attack all over the area. It lasted for four hours, with successions of aeroplanes thirty to forty strong; one Master Mariner made the note, ‘Over 100 bombs on ships near here since 5.30’.

At the home ports, 670 troop trains carried the soldiers away. Volunteer war workers provided mobile canteens to all these trains to give food, drink, sweets and cigarettes to all, and to send off telegrams for those who wished.

(John Masefield, The Nine Days Wonder)

When we got to Dover we were put into old customs sheds. In there were these ladies from the women’s services – the Red Shield Club – all the various ladies’ associations. I had no tunic – I’d lost it – and one of the elderly ladies took off her fur coat and put it round me whilst I sat down, and gave me a cup of tea. Then she produced a stamped envelope – stamped and sealed – and she said, ‘Right. Address it to go to your wife or whoever. Put the message on the back. Use it like a postcard – it will get there quicker.’

(Corporal Frank Hurrell, 3rd Field Army Workshop, RAOC, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

2nd Lt Jimmy Langley of the 2nd Coldstream Guards, whom we last met on 30th May with his eccentric Brigadier, was wounded while part of the rearguard: ‘I had just fired five most satisfactory shots, and was kneeling, pushing another clip into the rifle, when there was the most frightful crash, and a great wave of heat, dust and debris knocked me over. A shell had burst on the roof.

There was a long silence, and I heard a small voice saying, ‘I’ve been hit,’ which I suddenly realised was mine. That couldn’t be right; so I called out, ‘Anybody been hit?’

A reply from behind – ‘No, sir, we are all right.’

‘Well,’ I replied more firmly, ‘I have.’

By the time 2nd Lt. Langley was wounded on 1 June, the La Panne casualty clearing station had been evacuated. That explains how he came to be lying in an ambulance in the driveway leading up to Chateau Coquelle in Rosendael, a large house that BEF soldiers knew as ‘Chapeau Rouge’ or the Chateau. This was the temporary base for the 12th casualty clearing station for wounded soldiers about to be evacuated to England. It was overflowing.

(2nd Lt Langley’s story from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. More news of Jimmy Langley and the Chateau on 3rd and 4th June)

The homeward route was a wonderful sight. Hundreds of small craft of every description, making towards Dunquerque. The German bombers were busy dropping their loads all over the place. There were more than seventy enemy planes overhead dropping their bombs all round on us, like hail-stones, but our luck held good. We escaped undamaged. The gunner put in some great work with his gun and hit three enemy planes, two of which came down. I was just coming along Folkestone pier at 8.30 when a violent explosion occurred. Another lucky escape. A mine had gone off behind us. We had brought home 504 troops, seventy of them French.

(A shipmaster, quoted in John Masefield’s The Nine Days Wonder)

All the routes homeward were now under very heavy shell-fire. It was reckoned that the enemy had at least three batteries of six-inch guns near Gravelines along the coast to the west of Dunkirk, besides the heavy coastal guns in Fort Grand Philippe to the east. At six that evening the signal was sent from the harbour: Things are getting very hot for ships. It was decided that the harbour could no longer be used during daylight.

A naval officer had the heart-breaking task of telling the men waiting on the jetty that they would have to go back and wait for night to fall. In spite of the appalling fire the lifting on this day was a record; we took away 61,998 men. Our loss in troopships, destroyers and mine-sweepers sunk and damaged was very heavy.

(John Masefield, The Nine Days Wonder)

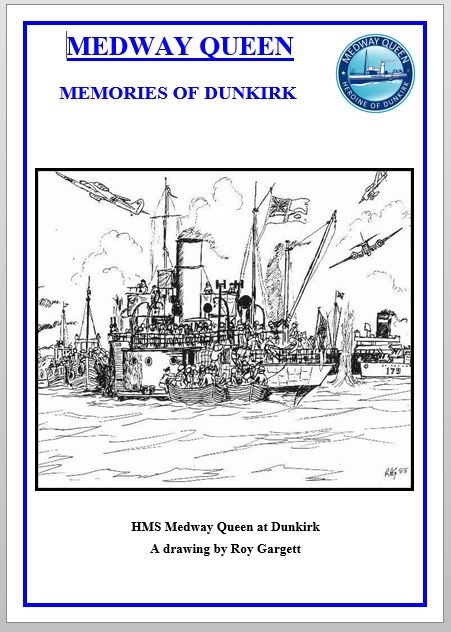

This postcard from the evacuation is another from the series contributed by the Medway Queen Preservation Society. More stories in a feature on HMM Medway Queen.

Thousands of men stretched away behind us. But we failed to move forward. Only the wounded were got away that night. As the hours went by, the spirits of all must have been sinking. Mine certainly were. Sleep was impossible. It was just waiting, waiting, waiting.

(Gunner Lt Elliman, from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk)

Sapper Alexander Graham King, the mad hatter, finally finished his self-imposed tour of duty entertaining the troops on the beach for seven days with his accordion, and got on board a ship for home.

(from the Imperial War Museum archive)

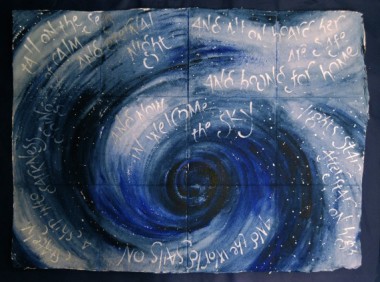

Dunkirk Phossils 67 – Basil, John and Kate Bonallack, by Charlie Bonallack: image from family photograph hand-painted on porcelain fired to 1280°c. This image is a detail: more Dunkirk Phossils here.

I went in the pub the first night I came back from France, and the landlord said to me, ‘Oh, we thought you’d been took prisoner.’ And old Bill, the postman, took one look along the bar. He said, ‘I told you if there’s only one bugger come back it’ll be him.’

(Senior Aircraftman James Merrett, Ground Gunner RAF, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

Tamzine was the smallest boat surviving – an open fishing boat from Birchington measuring 14′ 7″, she can’t have held many men in each trip, but must have ferried hundreds from the beaches to the waiting ships. She’s now in the Imperial War Museum, surrounded by massive tanks.

(Ships’ stories from several sources including the website of the Association of Little Ships of Dunkirk. More little ships’ stories throughout the nine days)

All sorts of craft were coming round the buoy, all fully loaded with troops. A batch of about twenty Belgian fishing-boats bore down, the leader asking us the way to England. I sung out the course, and told him to follow the other traffic and he would be all right.

(Observer quoted in John Masefield’s The Nine Days Wonder)

The Imperial War Museum Photo Library has a remarkable collection of photos taken at Dunkirk, some of them aerial photos taken from RAF planes showing the armada of little ships and the shoreline, some taken by photographers on the ships showing the queues of men up to their chests in the sea, some of the lines and formations of men on the beaches. There are the burning oil stores and the wrecked town, the Chateau and the debris on the beach.

Some photos were taken by German photographers and show the ruins of Dunkirk after the evacuation, some are of battered returning little ships being towed up the Thames towards Waterloo Bridge, others of soldiers on their way home. These photographs tell eloquent stories of their own, not least of the courage of the photographers.

(Seven photos from this archive can be accessed here.)

02.35 Anchored off the N. Goodwin Sands in response SOS from Golden Gift ashore high and dry with 250 troops on board. Took off troops in motor-boat in five trips and returned to Ramsgate to disembark troops.

11.00 Proceeded to Bray east of Dunkirk and anchored there 14.30. Shelling from Nieuport batteries. Embarked 900 British troops. Heavy air attacks and 6″ shelling throughout afternoon, necessitating shifting billet on two occasions.

23.30 Weighed. Two magnetic mines dropped by plane close to.

5.00 Disembarked troops.

Remarks. Embarking troops was carried out under difficult circumstances owing to heavy shelling, air attacks and swell running, which made boat-work very arduous. The spirit of the officers and men was excellent. Ratings volunteered from the stokehold for any duties required.

(Commander KM Greig DSO, RN from the log of HMS Sandown)

Little has been written about the doctors and nurses who dealt with wounded men rescued from Dunkirk. There were not enough beds for all of them in hospitals near the main ports in Kent so many casualties were transported to other locations around the country. Nurse Harker, then 29, never forgot the day she met the first Dunkirk hospital train that reached Whalley in Lancashire. As the train, covered with red crosses, steamed into the station, she asked a colleague, ‘Why ever have these poor things had to come all the way to the north of England after all they’ve been through?’

The answer stunned her. ‘Because hospitals in the south are being emptied for the invasion.’ During the first night after the sixty-four Dunkirk survivors were brought in, Nurse Harker and the other nurses were rushed off their feet trying to deal with their patients’ physical needs.

(from Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Dunkirk. More from Nurse Harker tomorrow 2nd June)

At Dover when we arrived, there were a whole series of trains. All the units had been dispersed and one hadn’t got any of one’s own men – one was isolated, and we were simply told, ‘Each of you get on the train and get up to London. You’ll find the RTO at Waterloo, and he’ll tell you you’ll have a couple of days to go home, and where you’re to assemble to join your new units.’

So we went up in the trains – they were full of civilians who got in and were going to their office in London. Sitting next to you, there might be a man who was going up to his bank. One very nice man, a civilian, pressed into my hand two half-crowns – which was rather nice.

(Captain Anthony Rhodes, 253 Field Company Royal Engineers, from Max Arthur’s Forgotten Voices)

The light was going fast. She pushed the accelerator harder. She didn’t want to arrive in Bridport in the blackout. Suddenly as she turned the corner she was forced to change down to bottom gear by the mass of men jamming the narrow streets and strolling in the roadway. She pressed the horn to break a wedge through the khaki ranks.

A group strung out in front of her wheeled to face the car bringing it to a standstill. She was half aware that those on the pavement were standing still too, that she was surrounded by weary men in what she saw now was torn and stained battledress, their chins stubbled and their eyes red in the sooty rings of fatigue over the drawn cheeks. She saw too that they weren’t just tired but angry. The man in front of the bonnet with one stripe on his sleeve, opened his mouth in a soundless roar.

She had never seen a human being snarl, now there were faces all around her with the lips drawn back on tobacco-stained teeth. The soldier in front pounded on the bonnet. She knew the others were joining in, that the snarls were now half leers. She thought some of them were drunk. At any moment they might wrench the door open and drag her out. The squaddie beat his fist on the bonnet of the Morris again.

But one of his mates was pulling him off. The boy bowed a little towards her and waved the car on with an elaborate satirical gesture. She began to inch forward hearing the catcalls and feeling the car rock as others thumped on the side panels while she crawled between them. Then she was through the press and out into a clearer stretch of road. ‘East Street’ he’d said and there it was. She drew up outside the pub but was shaking too much to leave the car. She leaned against the glass side panel and realized that she had begun to cry. When Harry opened the door she almost fell into the street.

‘What’s up? Has anything happened?’

‘I ought to be asking about you. It’s just that I ran into a group of soldiers coming through the town. I thought they might be going to drag me out of the car and rape me or lynch me or something. They seemed so… angry.’

‘They are; bloody angry. They’ve been beaten. No army likes that. It’s being treated as a kind of victory here, plucked from the jaws of defeat, all that stuff, but they’ve been there and back. The beaches were hell but it was hell even getting through to them. Many of the chaps feel betrayed. Some of the officers left them to fend for themselves while they saved their own skins. All armies are like that in defeat, and victory too. There were nasty scenes as we withdrew and began the evacuation. Not everyone of course. Some units marched on board as if they were on the parade ground.’ He upended his glass. ‘Nothing’s been said here. And you mustn’t say anything either. To the rest of the world it’s got to look like a heroic and orderly withdrawal, not a rout, or Hitler will be down our throats even faster; he’s bound to try and invade if we don’t chuck in the sponge. The French will give in quite soon.’

‘We won’t, will we?’

(from Maureen Duffy’s Change)

I quote Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke: ‘Had the B.E.F. not returned to this country, it is hard to see how the Army could have recovered from the blow. The reconstitution of our land forces would have been so delayed as to endanger the whole course of the war.’

(Arthur Addis, from his account of his war experiences in a memoir for his family)

Within little more than an hour on 1st June we had lost three destroyers, a Fleet minesweeper and a gunboat, and four destroyers had been damaged. Almost immediately after this, the French destroyer Foudroyant was in her turn hit by the dive-bombers and in her turn sank. Two hours of disaster – nor was it the full tally of the day.

The rate of loss was too heavy. It could not continue. There was no question of goodwill involved: it was a question entirely of ship reserves; we no longer had the ships. It was decided that no further operations should take place in daylight along the beaches, as the rate of loss had become too heavy.

On this day we had lost in two hours the equivalent of the loss of a small campaign, a sharp naval action. With the ships had gone many of their own crews, and with them had gone very many more of the soldiers they had picked up at such cost of courage, of effort and of life. The wastage in drowning men alone was too great to be continued.

(from Dunkirk by AD Divine)

1st June. Set out, sent back due to heavy shelling from Gravelines, set out again 10pm, took 1600 troops from pier. It was rather awful as there were now so many wrecks in the harbour.

(Captain G Johnson, on board the Royal Daffodil. More from Captain Johnson’s extraordinary daily journeys to Dunkirk tomorrow, 2nd June)

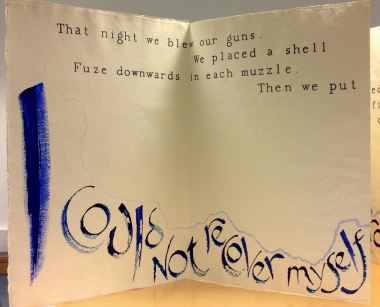

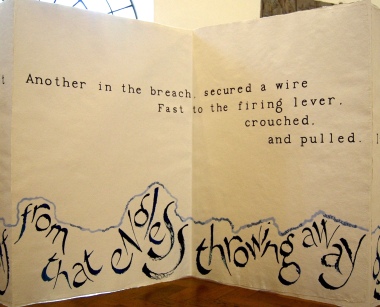

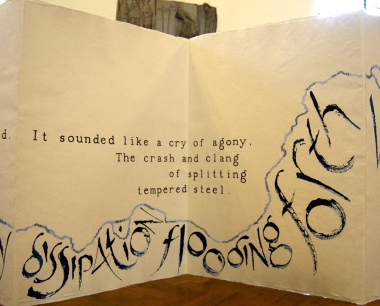

Tall ship – artist’s book by Liz Mathews, text by Valentine Ackland

from Night at Dunkirk

France under our feet like a worn fabric

Was little by little denied our steps

In the sea where the dead with seaweed blend

Bob the overturned boats like bishops’ caps

One hundred thousand men bivouac on

The sky’s rim and the water extends

Off into the sky the beach of Malo

There rises in darkness where horses rot

A sound like the stamp of migrating beasts

The crossing gate lifts up its striped arms

The hearts we have are but half a pair

I remember the eyes of those who embarked

Who could forget his love at Dunkirk?

The sand does not know the scents of spring

And now May dies on the Northern dunes

(Louis Aragon, June 1940, translated from the French by William Jay Smith. Thanks to Neil Astley of Bloodaxe Books for sending me this poem.)

To read today’s comments, or add one of your own, please go to 1st June 1940 – Homeward in the menu top left, and you’ll find the comments and conversations relating to today’s news at the foot of the page.

Tomorrow, 2nd June 1940 – Tatter’d colours